nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Reviews

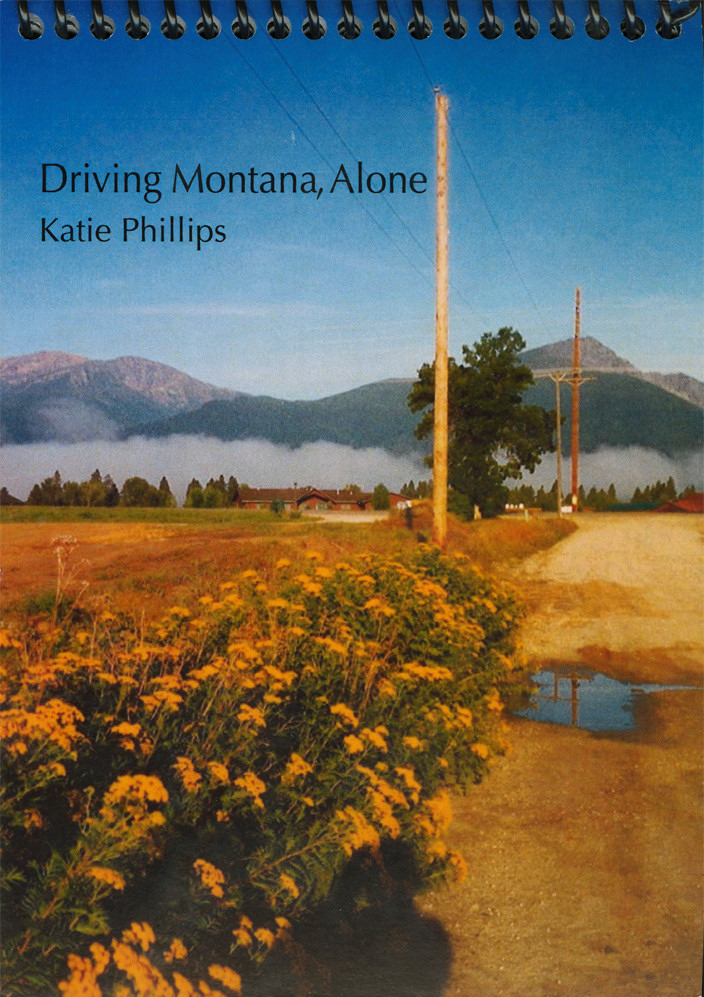

Driving Montana, Alone

by Katie Phillips

Driving Montana, Alone

by Katie Phillips

Slapering Hol Press, 2010; 41 pages; $12

ISBN: 978-0-9820626-3-0, paper

http://www.writerscenter.org/driving.html

Reviewed by Lynn McGee

Katie Phillips' new chapbook, Driving Montana, Alone, winner of the 2010 Slapering Hol Press Chapbook Contest, travels through a narrative landscape marked with images clear as signposts, both heartfelt and dispassionate. The beauty of the poems' simple observations is satisfying in and of itself, but Phillips transcends that beauty by letting it settle quietly amid her well-earned views on grief, and creating continuity, when life fragments.

On first read, it's that emotional narrative underlying the vivid, perfectly imaged poems that is most resonant. On second and third reads—it's a book to return to—Phillips' skills beyond the observational begin to be more apparent. Of course it's the "Alone," in Driving Montana, Alone, that alerts the reader to her theme of displacement and loss, but it's the "Driving" that points to another strength in the work, its startling shifts in perspective—she keeps changing who's at the wheel.

In the opening poem, "Raccoon," Phillips begins forthrightly enough:

By the cemetery, I hit him.

The reader is complicit in her horror—tempered with fascination—at having struck the animal with her car:

He did not make a sound,

just wrapped his striped tail round and

dipped the tip in the blood he was becoming.

Next, though, after the speaker has turned the car around to put the animal out of its misery, we trade places with the raccoon—and through this vantage point, Phillips makes a much larger, even metaphysical statement:

My headlights must have seemed

like distant moons, then blazing suns—

then music of the spheres.

Likewise, the perspective flips in "Explanation." The speaker addresses a "you," whose mother is dismayed by his less-than-sunny nature—

…Your melancholy confused her,

who waited all year for verdancy

and lilacs…

In the last stanza, the perspective switches to that of the "you" as an infant, that "autumnal" disposition permeating his world view, even in the crib:

Through your new eyes, even

your mother's face was shaped

like a leaf, falling toward you.

In "Driving Montana, Alone," Phillips does much more than play with the perspective, though she does that, too, in the final stanza:

…It seems only you

could know why my eyes fill the road

with tears again when a flock of swallows

swoops through an open barn door

and rushes out the gaping roof.

It isn't her eyes that fill with tears, it's the road; and in that small detail, grief, in its enormity, is flooding not just the speaker's feelings but the world at large.

In "Kodi," a poem all the more sad for its unsentimental stance, the speaker grieves for a deceased pet. We observe a back yard and see rabbits not just through the dog's eyes but through the diminished capacity of his failing final days:

Three rabbits browsing in the back yard

choked me up. One near

the bushes, where you slept

those long afternoons, held still,

and I lost him when I looked away.

Mistaking a pebble for his eye, I knew

for a moment your final

days, when nothing felt real

until it moved.

And in "Alzheimer's Unit," we first view a woman with Alzheimer's through her son's point of view, then find ourselves trapped in the perspective of the woman herself, a view which narrows even further as:

her folded hands know only each other.

Another considerable strength in these poems in their ability to use seemingly simple observations to open windows on vast, sometimes hard-to-name states of being; concepts as mysterious, for some, as death itself.

Looking again at the unforgettable opening poem, "Raccoon," we see that the injured animal:

just wrapped his striped tail round and

dipped the tip in the blood he was becoming.

He isn't dying; he's becoming reorganized. And in the same vein, a statement is being made about the very nature of existence—you can't destroy matter; or to some, "We don't die, we become something else."

"Raccoon" ends then, with this unexpected, but perfectly natural moment, an observation of the moon introduced in the previous stanza:

…I thought if, heavy

with haze, it crashed down

on this paved planet,

there would be no room

for me.

Those lines establish the world as a setting constructed for movement (a "paved planet"), as well as for the displacement that comes with leaving behind the familiar, or losing one's place; geographically, romantically—often both.

In the midst of all this loss—of home, of other, even of self—Phillips affirms identity that is internally, not externally, defined. "The best I can hope for," she writes in the poem "Moab,"

…is life as a claret cup cactus…

proof of myself in this sandy draw—

color, my only explanation.

Similarly, in the poem "Explanation," where the mother waits "all year" for lilacs, the speaker is defined, or defines herself, through the code of color, which is quite enough.

That points to one source of the beauty of this book. Phillips well knows what's too much, and what's just enough. The poems are spare in images, but generous in effect. They leave the reader with a sense of recognition, while the universe they create is solely her own.

One of the unusual things about this book is that Phillips creates that universe with photographs, as well as poems. Over 15 black-and-white and full-color shots are interspersed with the poems, extending their momentum with views of the Montana landscape—many as if seen through the windshield of a car; winding roads, snowy mountain vistas, fields of wildflowers, and other scenes. All were taken by Phillips, except for the title page shot, which is by Ron Rapp.

Overall, the rural landscapes of the photos, and of the poems themselves, invite a kind of yearning, or homesickness. More subtle than Country Western lyrics, there are nonetheless moments when Phillips' work allows a wry, almost self-deprecating tone, as in "At Last, Some Recognition," where she writes,

…and you are leading me

back to the only place I've never left

or in the rueful "With my fingertip, with my own gravity," where

Someone else brushes her teeth,

globes of water dropping,

where I stood, and the dog,

still mine, his tail slapping,

sleeps at the foot of their bed.

Whatever loss conveyed by Phillips' work, there is never regret, bitterness, or blame. In fact, Driving Montana, Alone reverberates with compassion. "What We Knew" looks at the cruelty dealt to:

…baby monkeys, some given soft cloth

mothers, others allowed wire dummies

and in the end, Phillips writes,

…only scientists needed monkeys

to prove what we knew by holding hands.

Similarly, in "Reincarnation," a mouse is cornered in a house and two people argue about what to do:

You wanted to be quick;

I wanted to leave the door open.

And finally, in the book's last poem, "Winter Morning," she integrates loss with hope:

When you leave, I save an impression

of you, the dent in the white pillow,

yes, but also footprints in new snow,

and a certain sense on my hand,

for you to slip back to, for you

to know what I keep open.

It's impossible not to want to read more of Phillips' work, after finishing this stunning chapbook. Driving Montana, Alone is a road trip straight into the heart of loss and love. The view is gorgeous, the route skillfully mapped. I would return there, in a heartbeat.

Lynn McGee poems appeared recently in The New Guard—one a finalist and another a semifinalist in that magazine's contest, judged by Donald Hall. Other poems of hers have appeared in the Bijou Poetry Review, Kennesaw Review, Laurel Review, Ontario Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Phoebe, Pittsburgh Quarterly, Southern Anthology, The Sun, West Coast Review, and other journals. Her chapbook Bonanza won the 1996 Slapering Hol national manuscript contest; she received a MacDowell fellowship and earned an MFA from Columbia University.