nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Fiction

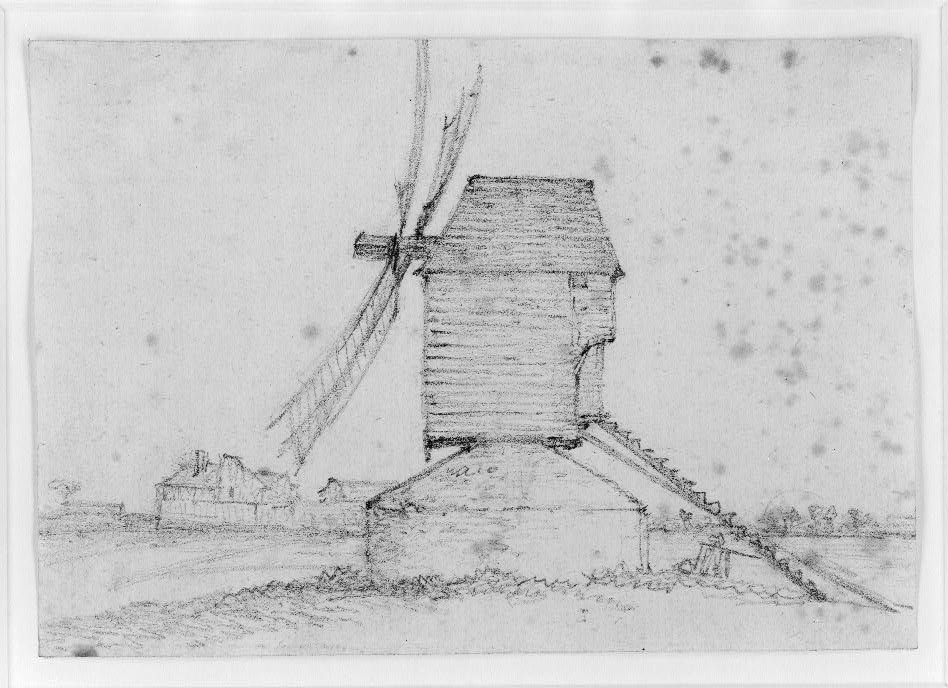

The Blower

Ryan C. Christiansen

He felt silly beneath the windmill, lips pursed and exhaling. He only whistled and accomplished nothing. They must think I'm blowing kisses at the mill, he concluded, and thought of her. If he could get his wind back, he thought, the king's daughter might be impressed. It was his breath that had made her penniless, after all. He would use his breath to win her heart.

He pursed his lips in every way, changed the angle of the blow, drew long, blew short, and tried every exercise and contortion to change the way the wind left his lips. He could no longer shake the leaves from a tree so much as blow a leaf from his hand, and it puzzled him. The windmill would not turn, and the woman he pined for remained out of reach.

In gilded cloak and pantaloons, soiled and soaked then baked in the sun, he stood. He was caked in dust, and his beard hung low to a small cave below his rib cage, where his belly had been. He was a skeleton, an old tower waiting for a stiff breeze to push him over. He'd been there so long, he'd forgotten how to move his legs. He feared to take a step ‘lest he fall from exhaustion.

It had been months now since he'd blown over the king's men and taken home the loot. Standing on the road in the face of a regiment, he blew down the chargers and pikemen with just one gust from his throat. But now he couldn't make the fan of the mill budge at his breath, not even from 100 feet beneath the sails—much less from two miles away and while sitting in a tree.

With one-sixth of the king's wealth his own, he could afford anything he wished. Maids and mistresses leaned on him when he approached. "There is the man who stole the king's fortune!" they cried. The other five soldiers of fortune took their lots and journeyed to the ends of the earth, but he stayed. He remained captive to the thought of the former princess as his love.

He'd hired consultants: magicians, priests, and witches. Had it been magic or the hand of God that gave him the gift of gales? The outcome of his consultations were shallow, mere suggestions: change the angle of your stature in relation to the mill; wait until spring tide, when the moon's pull might be helpful. There was nothing they could do to help him regain his blow-hardiness, but they were willing to accept additional payment to continue their research. He, too, had become penniless. Alone.

His heart beat against his will, and so he stood now in front of the mill, heels together, resisting, the pull of the Earth insisting that he quit this gamble. Where the blood collected, his hands felt bloated, but he raised a stiff palm to his heart and vowed to make one last effort to turn the fan.

He drew deep. The air swirled in a vortex around his tongue, his lips pursed in muscle memory. He thought, For her, and nearly chuckled. As if she might want a penniless blowhard, he concluded, and then let forth a breath so soft a feather mightn't tremble in its wake. Indeed, he wasn't sure whether he exhaled at all. Perhaps he only believed that he breathed, but still he resolved to hold on to the expectation.

Something familiar wafted out from his lips, a slight tingle of humidity, some force in the ether. He felt like he'd caught the end of a ghost. A relief, he thought.

And with the end of his lungs, he let go. He closed his eyes and listened, but the quiet Earth didn't answer. Even the birds stopped chattering at the drop of evening.

Just then, the windmill creaked.

Ryan C. Christiansen is an MFA candidate at Minnesota State University Moorhead in Moorhead, Minnesota. He is a career journalist and technical writer. He lives in Fargo, North Dakota.