Reviews

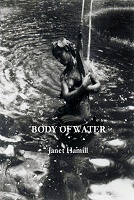

Janet Hamill's Theater of Dreams

Bowery Books, 2008; 88 pages; $16.95

ISBN978-0-9800508-6-8, paper

Photographs by Patti Smith

Reviewed by Diana Manister

One of the few American poets who work the borderland between rationality and dreaming, Janet Hamill writes poems whose meta-theme is the active presence of the subconscious in psychic life. Her new 88-page volume of poems, Body of Water, her fifth, further establishes her as an heir to the insurgent counter-tradition in poetry dedicated to the belief that reason is not the only reliable way to achieve knowledge.

Hamill's work is a contemporary iteration of the oneiric poetic tradition dating back to Rimbaud. Though Baudelaire and Breton are among her artistic ancestors, to call Hamill's work Surrealist or Symbolist would be reductive. The dream state has appeared in art since ancient times and has been taken as a subject by artists throughout history, including those to whom Hamill pays explicit homage, among them Federico Fellini, Buster Keaton, Georgia O'Keefe, Jack Keruoac and legendary rocker/poet Patti Smith, whose photographs — which read like stills from dreams — provide stunning visual equivalents of Hamill's poetry.

Symbolism and Surrealism are not simply art movements, they are functions of the human mind. From earliest times, preconscious levels have been tapped as sources for art. Calling the Lascaux cave painters Surrealists, or Byzantine icon painters Symbolists, would be entirely accurate, but because those labels are associated by art historians with specific modern styles, the term oneiric art serves as a broadly inclusive indicator.

Kin Spirits

A clue about Hamill's approach can be gleaned from the following poem, which begins with the title of an actual Fellini biography. Rather than listing facts about him, however, she voices his artistic vision as she sees and shares it:

I, Fellini

who am nothing

without you

have been hired

to shoot a masterpiece

and I will

lift it off the storyboard

from the comic strip

in my mind —

…Life is a great white movie screen

Let's step into it together!

Cinema is an eminently suitable oneiric medium; Roland Barthes describes the passive movie audience as being in a "para-oneiric" condition, prepared to enter a dreamlike state, not unlike the original audience for cave art. Fellini, who acknowledged as an influence Carl Jung's writing on the collective unconscious, said that in his films, "every object and every light means something, as in a dream." Fellini's iconography comprises many archetypal figures: in La Strada, the surly strongman Zampano in some scenes becomes Animus incarnate and the innocent Gelsomina sometimes suggests a Christlike figure. In Fellini's 8 1/2, Seraghina briefly morphs into The Seductress, an image of pure female sexuality.

The I in I, Fellini is not the egopoetic of confessional poetry, but rather the impersonal self of the artist as vates, the vision-bringer who provides access to twilight mental states (Leonardo is said to have worked on the Mona Lisa only at dawn and dusk.) The one who speaks I, Fellini is the Lacanian subject of the intra-dit, the I linked to the unconscious, not the Freudian personal ego. But it is also something even more mysterious: the I of shared subjectivity, the intra-dit of artistic identification, like Picasso's saying "Yo El Greco."

Fellini and Hamill are both artists on an Orphic journey to the mind's crepuscular underworld, from which they bring back characters, situations and images that baffle the intellect. In myth, Eurydice withdraws back into the dark unknowable when Orpheus looks back at her. Because, like Eurydice, subconscious content tends to disappear in the light of conscious examination, oneiric artists avoid articulating their artmaking process. "I've said enough," Fellini says in the poem, "let's begin before we destroy this film with talk."

Hamill, like her artistic kin Fellini, acts as a passive recorder of received imagery, which, as Lacan observes, carries messages between the diurnal and nocturnal psychic realms. Unlike the composition of the Postmodern pastiche, Hamill's poems cohere as a nexus of associated feeling tones. Working spontaneously while maintaining the work's continuity requires a poet to assess the affective register of each poetic element that enters awareness for its fittingness for the poem at hand, exercising aesthetic control in a way only the artist with unusually keen intuition and practiced craft is capable. This is not automatic writing.

Hamill's compositions fit Umberto Eco's definition of "open work": internally dynamic and psychologically charged fields of meaning, rather than linear sequences of signifying strings. She welcomes adjacencies that a frontal-lobe poet would likely dismiss as unrelated, like the unexpected concatenations of "the still asylum of a blue sound" in "Sea Fever."

Who's Enigma?

Another Hamill poem about a filmmaker, "The Enigma of Buster Keaton," brings readers to an eerie revelation by means of a brilliant trope. The poem's narrator is riding a train (Keaton loved trains and often used them in his films.) She looks up from a book she is reading titled The Enigma of Buster Keaton, and imagines the genius of silent films being peppered by reporters with ignorant questions about his art: "Why don't you use a script?" they ask, and "Can you explain your lucidity?" — absurd requests for impossible explanations of a preconscious process. (Fellini once said, "Don't tell me what I'm doing!")

Hamill's daydreaming narrator imagines visiting Keaton in his famous California villa where she finds "Potted palms. Persian rugs. The endless procession/ of extras dancing to a jazz band." There she finds the book she had been reading on the train, its title, The Enigma of Buster Keaton, radiant with dream-symbol significance. Holding a blue umbrella, Keaton floats in the breeze before an open window, turning graceful somersaults. "Where do you go when you're not dreaming?" the narrator asks him. Or perhaps he asks her; the speaker is indeterminate, an ambiguity of subjecthood that creates more, not less meaning in the poem. It is at this point that dream turns into epiphany: the narrator is not only visiting Keaton, she is visiting herself.

Jung said symbols manifest unknowns that cannot be made known to the intellect. In "The Enigma of Buster Keaton" the title of the book resonates with symbolic significance, carrying more meaning than can be unpacked. The enigma in question comprises many mysteries, one of which is shared subjectivity. The enigma of Buster Keaton is the enigma of Janet Hamill, whose waking dream the reader also dreams.

The question Hamill's poem asks is this: Who directs a dream, who dresses the sets and plays all the parts, and who watches it, if not the I transmuted, transported and multiplied?

As in dreams, imagery in "The Enigma of Buster Keaton" has shifting polyvalent meanings: the blue umbrella, like Wallace Stevens' blue guitar, bears among other connotations that of imagination itself, which can defy logic and natural law. The dreamer herself is Buster Keaton, at the same time she is the ignorant reporter who questions him, and all of the extras dancing to the jazz band. But decoding will never bring the poem's meaning into the realm of the intellect; translating the poem into prosaic discourse would effectively destroy its meaning. (A possibly apocryphal story tells how Robert Frost, being asked after reading one of his poems what it meant, simply read the poem again without comment.)

Hamill's poems "resist the intelligence almost successfully" as Wallace Stevens said good poems should. The phenomena they report are shifting and metaphoric; her unlikely concatenations emerge into the poem from the disjunctive undermind, connected by feeling, not logic.

Unlike a character named Greed in a morality play, or a stop sign, a symbol doesn't stand in a one-to-one relationship to something else; it condenses a multitude of meanings. A symbol is a figure with manifold affective resonances, like the eye atop the pyramid on the dollar bill.

Symbolism in American Poetry

Less popular in America than realism, Surrealism and Symbolism nonetheless have exerted a powerful if unacknowledged influence on many American poets. Even that champion of realism William Carlos Williams, who generally mended his wild French ways after his early experimental book Kora in Hell, still penned an occasional Symbolist trope: a city is a symbol throughout his book Paterson, for example, and his famous poem "The Great Figure," is one of the few purely Symbolist poems written by an American Imagist, and served as an inspiration for Charles Demuth's painting The Figure 5 in Gold. In both the poem and the painting, the golden 5, which Williams saw on a passing fire truck in New York City, appears as a mesmerizing icon about which little can be said.

Why Symbolism and Surrealism were welcomed into modern European poetry but were largely banished from advanced American poetry has everything to do with our pragmatic national character. American culture values the useful, the saleable, solid things over shades, trademarks and logos, not symbols for states of being. And silence, which sells no consumer goods, is anathema to a culture based on marketing. Hamill's poetry subtly addresses this concern. In "I, Fellini," for example, the director asks "What is the role of silence in all this noise?"

Both French art movements reacted against the commodification of the individual that occurred with the rise of capitalist cultures, which has little use for dreamers. In her book Surrealist Women, Penelope Rosemont challenges the common misperception of surrealism as a refusal to accept reality. Rather than indulging in bizarre novelty "It insists, rather, on more reality" she writes. "If civilization persists on its disastrous path — denying dreams … glorifying authoritarian institutions…and reducing all that exists to the status of disposable commodities—then surely devastation is in store not only for us but for all life on this planet."

Rosemont's comments apply to oneiric art generally. Dreaming has great utility. On a personal level, dreams warn us when our lives are out of balance: an explosion may signal that the dreamer should reduce the pressure of repressed rage in waking life, a stray kitten may indicate a neglected need for tenderness. On the cultural level, a society that acknowledges inner realities can better understand collective irrationality before forces like greed and aggression grow to destructive proportions. Oneiric artists dream the culture's dreams, restoring the poet's mantic function in society.

Robert Bly's Deep Imagism was an admirable attempt to create what Gregory Orr describes as "a poetry structured by symbolic imagination and making extensive use of symbols … It was the poet's job to bring from the … unconscious those images that could enable humankind to face and understand itself." The movement however was trivialized not only because Bly himself politicized and sentimentalized his poetry but because it degenerated in the hands of younger poets into what has been called vague "pink fog" poetry, instead of the vital counterbalance to materialist culture that Bly envisioned.

Some American artists however have sustained the vision throughout their careers. Poets like Janet Hamill are oneirauts who travel through lucid dream worlds while awake, bringing back content of universal, not merely personal, significance, as anglophone Symbolist T.S. Eliot did when he described the flat colorless world of the neurasthenic Prufrock and the collapsing objective correlative culture of The Waste Land's psychologically disintegrating narrator. After the devastating barbarity of WWI, Eliot's poems expressed society's nightmare, and his Hyacinth Girl, a symbol of the animating life force, expressed collective hope. Critics who have dismissed Eliot's work because of the author's well-known personal sins may have dissuaded new poets from following a shamanic guide to the underworld.

"Immensity is a category of poetic imagination."

In his book The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard examines the phenomenology of poetic imagination, particularly its spatiality:

To give an object poetic space is to give it more space than it objectively occupies. Daydreams of immensity result in enlargement of consciousness … Immensity is an inner state. It loosens the ties of time and space.

"Kerouac," an homage to one of Hamill's early culture heroes, begins in a standard Imagist manner with a description of material reality, but by the second line the poem's scope radically enlarges by means of expansive spatial imagery:

I had nothing I had four walls on St. Mark's Place

a bottle of Calvados and the silence of the universe

I had nothing but I had you

From sea to shining sea east to west north to south

Atlantic Pacific Arctic Antarctic the Indian Ocean

and the last mar incognito over under inside

and out beyond everything I had you I had words

lines and paragraphs rushing down mountainsides

high above the timberline from Desolation Peak

to 242 choruses of blues for the Buddha

What other contemporary poet, with the possible exception of Ashbery, can so enlarge a poem's focus from intimacy to immensity in two lines as Hamill does in "Kerouac?" It is easy to see why Fellini and Keaton are her semblables: Marcello, trapped in his car in 8 ½, astralizes himself and floats in the sky; Keaton's stunts, often performed at great heights, defy natural law, escaping what poet Paul Eluard called "the solemn geographies of human limits." The self in imagination can fly, divide, bilocate, visit legendary artists living and dead, travel to other times and worlds that were once or never. Baudelaire sprinkled the word vaste (vast) throughout his poems like seasoning. Describing his experience of inner immensity, he wrote: "I felt freed from the powers of gravity and succeeded in experiencing the voluptuousness that pervades high places."

Form Follows Function

Hamill's style effectively serves her content. Defiant of poetic minimalism, she refuses to trim her language to fit literary fashion. When she writes lines like A handful of magi/rowing a boat through a neglected passage of longitude in "Dark Skies" or Big Sur's ocean roar/of vowel sounds from the far side of eternity/the waves laying better than a thousand transcendental/diamonds of compassion at your feet in "Kerouac" her writing is fulsome and lush, just short of overwritten, an in-your-face reveling in artistic freedom. Extravagant language is not only appropriate for the expression of exhilarated states, it is necessary. Terse, retentive phrases are unlikely to communicate exuberant freedom, which requires a measure of semantic abandon.

Fellini stated it succinctly: "A different language is a different vision of life." Minimal, laconic lines banish the expression of affective and sensual intensities from poetry, as if they were shameful and censorable, as sex was in Victorian literature. The reaction against Romanticism has perhaps been carried too far; the anathematizing of the lyrical impulse in advanced poetry has produced some of the most constipated poems ever written: flattened affects squeezed out in tight, overly controlled utterances. One of the ironies of contemporary literature is inherent in poetry that theoretically rejects official control of individual subjectivity but in practice censors its expressive range, privileging poetry produced by the "thinking cap" neo-cortex.

Not so Hamill's poems. In "Door to Door," for example, the imagination is free and language is lush and luxurious:

…in the deserts of Venus

a door opens on a pale horse turning pink in the rosy glow

of the setting sun all that is stalled lifts off in dreams

birds of ruby glass alight on the pilings of a pier

over the Hudson a door opens on the palms

of my hands scarred with hearts and wands crosses

glyphs and planets assuring my good fortune

to get lost in a movie palace circling a sarcophagus

filled with sand from the Valley of the Kings

deep in outer space a door opens on Neil Young

the sky pilot flying from point to point to fire the stars

with a gas torch igniter and all that is stalled

lifts off in dreams

Voluptuous sensuality, a sense of amplitude both inner and outer, occult mysteries, extreme states of ecstasy, "all that is stalled" in minimal poetry takes off in Hamill's poetry. Bachelard writes:

When the daydreamer really experiences the word immense he sees himself liberated from his cares and thoughts, even from his dreams. He is no longer imprisoned in his own weight, trapped in his own being.

"Door to Door" — with its nod to Neil Young — and "Blue Tango Shoes" — for Patti Smith — acknowledge rock music's enthusiasm for the oneiric approach; from The Beatles and Dylan to Goth and Death Metal, rock's poetic lyrics make liberal use of hallucinations, trips and visions.

"To What End Do I Declare Myself"

Hamill's poem "Altar Piece" expresses what Bachelard describes as "the concordance of world immensity with the depth of inner being":

Where the dark sea breaks into the dark night

I send up my sighs

In what repository of time trapped in what

latitude lost in the halls of a vandalized labyrinth

in what Tropic of Hazard or Rigid Inertia

over whose bowl of worms

do I stand repeating repeating

to what end do I declare myself to what end

Unlikely juxtapositions appear as in a nightmare, their relationships mysterious but compelling, united by the mood of a lone traveler lost in a vast "field of meanings." He was writing about Baudelaire, but Bachelard could have been describing Janet Hamill's daring poetics of inner grandeur when he wrote: Immensity is within ourselves. It is attached to the kind of expansiveness of being that life curbs and caution arrests.

By defending the freedom of imagination against ideologists of all stripes, oneiric art defends individual privacy and the value of silent reverie. It valorizes the artist's mantic power, devalued by realism and conceptualism, and it frees poetry from the deadening effects of intellectual analysis and commodification as novelty and entertainment. The "insurrection of the imaginary" as Rosemont terms it, acts as a counter weight to destructive collective rationalizations by reifying the value and grandeur of inner realities.

All of which is better expressed by Hamill's own words in "Boy Blue":

…Over the water, at the edge

of the dreamline, prevailing winds favor a crossing

go on ahead. The deepest chamber of the night

will restore your exhausted wings. Go on ahead …

Bowery Books is an independent press, founded by poet, professor and spoken word enthusiast Bob Holman, under the auspices of the not-for-profit Bowery Arts and Science, which also operates the Bowery Poetry Club in NYC.

Body of Water is available through all online booksellers including amazon and bn.com, and through the Bowery Poetry Club www.boweryartsandscience.org

Diana Manister is New York City poet who has performed at such venues as the late lamented punk rock club CBGB's, St. Mark's Church Poetry Project, The Living Theater, Bowery Poetry Club, the Lyric Recovery Festival at Carnegie Hall, as well as at colleges and universities.

A Contributing Editor of Big City Lit, she is also an elected member of the American Branch of the International Critics Association (AICA). Her poetry reviews appear regularly in The Modern Review and online at BigCityLit, about.com, small press exchange and artezine. Her poems have been published and exhibited in print and web publications including PoetryRevolt, Autumn Sky, Salonika, Big Bridge, Waterworks, The Cleave, snarke.com and others.

Her poetry has been anthologized in Compilations 1, The Best of 2008 Online Poetry published by Poetry Blog Rankings, and in an upcoming anthology of experimental poetry from Wordpress titled The Cleave Anthology 2008/9 for which one of her visual poems provides the cover art.