Fiction

Stoned

the first chapter from the novel by Jill Hoffman

I. I am a kind of burr; I shall stick.

(Lucio, Measure for Measure)

1. Mad Diamond

When I was young, I almost always had a headache. It was like a curse in a fairytale.

"When your prince comes, he will take them away," my mother said, putting a steaming washcloth on my forehead.

Now I think it was from rain, or my period. But then, knowing I had a tension headache would make me tense. I would wake up in the morning with a vague throbbing, and three days later it had turned into a migraine. My head would beat like two hearts.

I threw up into a mixing bowl.

I was twenty-five when I finally got engaged. My father used his influence to get the announcement of my engagement in the Times; he only succeeded, he told me later, because they thought my fiancé was the son of someone else. And the announcement, with a long-necked picture of the bride, was marred. They left out the 'u' in my first name.

Miss Mad Diamond

to wed

Daniel Farber

It made me wonder if I was mad to marry him. But I didn't wonder for long.

His hand covering mine, we cut the cake.

I went to a headache clinic; I had intimate conversations with young married doctors there. They gave me Fiorinal; it didn't work. It wasn't until much later that I encountered not only a cure but a substitute for headaches.

A psychologist with enormous breasts introduced my husband to grass. She was sitting in our living room on the couch. We had probably met her at a dinner party. Everyone had parties then, dinner parties. She liked my husband. A lot of women did. Daniel had a big bush of black hair, a pale thin face, a sharply chiseled nose, a narrow upper lip and a voluptuous bottom one, a square chin with a cleft in it. He wore turtlenecks under white shirts and jeans. It was the new Upper West Side look. Plus, he was submissive.

I had complained about my mother, who was busy ignoring her cancer and bleeding from the breast, and the psychologist said, "I wish I had a mother like that. All I ever wanted was an oddball mother."

I knew she also wanted my oddball husband.

Daniel handed me a joint. "You have to try this," he said, gasping and holding it in.

"Okay," I said and took a puff.

It was like flirting and sex and orgasm and profound insight all rolled into one. I had not known the sensation of 'vision' before. Now everything lit up like stained glass. When I smoked grass I understood George Tewkesbury's poetry perfectly. And I could write. As a poet you had to concentrate on making something into something else. You had to look at skyscrapers and imagine frozen vertical lakes; you had to look at parked cars from your high window and imagine buttons on a dress. Nothing was supposed to remain what it was.

My father said that all a writer needed was a pencil, a pad, and a bench to sit on. But he was wrong. After that first toke, I needed a joint.

"I ate chocolate all afternoon, then took a diet pill, and Antabuse," George Tewkesbury said as he came in the door. George Tewkesbury was the most "famously obscure" poet in America. Not since Tennyson had any poet sold more books. Every birthday I wanted nothing more than for George Tewkesbury to come to dinner at my house. Every birthday, my mother made a platter of butter cookies sprinkled with ground walnuts and sugar. She cooked turnips. I considered him among my closest friends.

His poems were written with scissors. A pair of scissors snipped away anything that made sense. But it missed some threads that clung. Hints. Inside information. Sexual moments you were privy to behind closed doors, the word 'semen' appearing in a blaze like an afternoon at the beach. I invited him on Halloween. "I have to admit," he said, "all the streets look pretty with so many little Frankensteins." It made me glad that I lived on the Upper West Side.

I bought ridiculous wine glasses for the dinner party, because they were pleated and rimmed with gold. Tiny, crenellated, they were no bigger than a thimble. My husband Daniel poured.

"What are these?" George drawled.

"New wine glasses," I murmured. George Tewkesbury made a wry face. After one sip his glass was ready to be filled again.

"Aren't those for sherry?" his lover, Peter, said. "I wanted to bring Gwendolyn, but Maud wouldn't let me," Sam Cohen complained. Gwendolyn was his new girl friend whom I hadn't met, but whose presence I was convinced would have ruined the evening.

George fancied Sam, who was our student.

"That's too bad. I would have loved to see her again," George Tewkesbury said. I had had no idea that he knew her. "Gwendolyn knows the names of all the different liqueurs," he said, in his slow contagious drawl. "I think that's a good sign."

His words were neon in the formal dining room. Whatever George Tewkesbury said was poetry. I wished I had let Gwendolyn come. I was tongue-tied all night. I couldn't think of a single witty thing to say. Finally I said, "I've been smoking grass since eight o'clock this morning."

"That explains a lot," the famous poet said.

Pot was the perfect excuse. It suited me. "Why are you always dropping stink bombs?" my father once asked. "To clear the air," I answered. I liked pot because it was like Aerosol. It disguised what my father called my 'stink bombs.' I could be myself because I was stoned.

I carried in the pots de creme for dessert.

"Another of Maud's intimate desserts," George Tewkesbury said. "Mousse is very hard to make."

"It was nothing," I said. The recipe was ersatz. In the blender cookbook, the brown-spattered page even spelled out, "Poh-duh-Krem."

After dessert, he went up to my bedroom to rest. I lay down beside him on the bed. "I know I'm the wrong sex," I said.

"Yes, you are," he drawled seductively. Then we went downstairs to the others.

George Tewkesbury's tongue flicked in and out between his lips like a snake's. He made a grab for my husband's leg. Then he grabbed Sam's leg. The evening was a success.

Even though he came to dinner at my house at least once every month, it was a tremendous coup for Daniel and me to be invited to George Tewkesbury's New Year's Eve party. I had found an irresistible sheer blue and gold blouse at Bendel's, with billowing sleeves and wore it without a bra. "You have nothing to hide," my mother assured me.

Luckily it was a small party. At midnight, the famous poet screamed for no reason, like a peacock. It was proof of his genius. At home in my billowing blue and gold sleeves I had felt like a mermaid, but now I wished the cushions of the couch were the sea and that I could dive to the bottom of it. Nobody did that in those days. No one went braless and exposed.

Another poet was there who was almost as famous as George Tewkesbury. He was horribly academic and formal, stuffy and getting a divorce. For some reason I felt compelled to mention to him that I knew all of his intimate history.

"I know that you've been dating my friend, Maggie," I said spitefully, as if to strip him of his honors, as if to expose him as I was exposed. He turned away from me.

"Who is that dreadful Diamond woman?" the poet asked a group of people who happened to include my husband.

"But, my friend, you could get hurt."

"I doubt it. I mean, I don't think I have a charmed life or anything, but you know, y'know? You can tell if somebody isn't right. I don't go with anybody who's drunk or high, if I can tell."

"She's my wife," Daniel replied.

We had been married fifteen years. I wanted to have great sex, like Louis the 14th, who had fireworks set off every time he had an orgasm. But instead after sex we always had a fight. Once, Daniel got out of bed, left our apartment and walked downtown to 42nd Street. He came home innocently enough with paperbacks that he hid. One day in his shirt drawer I found The Delivery Boy and the Dominatrix.

I envied the wives weeping in my building who had come upon their husbands in bed with another man.

"Why can't you just be gay?" I asked.

"Don't you understand, I want to service women," my husband said, pawing at my lap.

Soon I couldn't stand to be in the same room with Daniel. He had grown his hair long at my insistence so that he would look more artistic and unconventional. It made him taller because it stood around his head like an Afro. But now he just looked like a wild man to me. He wore jeans like a hippie, I thought scornfully. And a book bag like a schoolboy! Nowadays all sorts of men carry book bags, but then I didn't think I could love a man with a book bag. We separated. When he came by to find some papers, he dragged the file cabinet out into the tiny vestibule and stood in the hall squinting and searching through the drawers. Shortly afterwards, a pretty young girl, who was a student of Daniel's, served me with papers.

My mother was on her deathbed in the hospital for Joint Disease—she had refused to have her breast 'lopped' and had gone on a diet of raw greens— when I told her I was getting a divorce.

"I'm very happy for you, Maud," she said. "I want you to marry an equal." If I had any doubts she assuaged them. My mother thought I was perfect. "Your bad is someone else's good," she always said. "I don't think I spend enough time with Lily," I once said coming home late from teaching. "It's not quantity that matters but quality," she replied.

Then my mother died. I was angry at my mother for being crazy—it was two years before I could even mourn her—but she had been my main support, the one who made me believe in myself, who made me powerful. The world ended. I smoked grass. I had my own dealer who came to the house and had written a Tewkesburian book of poems.

By the time summer came, though I was sending my children Lily and Nathanial to camp, I was too depressed to sew on a single label. Lily stayed up all night and sewed the nametapes on all the shorts and t-shirts and linens and pajamas for her and her brother. I made my first mistake, like the first step I took in the dark feeling the edge of a swimming pool when I was five and falling in. Instead of devoting myself to my children, I put on a grey vintage dress and green sling back heels and got on a bus to Vermont to give a poetry reading. George Tewkesbury had gotten me the gig.

I was at Bennington College, for the July Program. I was a visiting poet for two days. I hadn't been back to Bennington in twenty-five years.

I gave the reading as soon as I got there. Then I was introduced to a bearded novelist, and I thought it doesn't matter about his beard, which looked scratchy, at least I wouldn't be alone that night. It would be an adventure that I would read about in his next novel. I heard someone behind his back mutter that the novelist was a redneck. Was a 'redneck' someone from Appalachia? I was separated and single and I had to have an affair. I looked up at the redneck smiling; he smiled back. His liking me meant I would never be alone. I was drinking wine in a plastic cup. I turned around to get a Triscuit and he was gone.

"Are you looking for the novelist with the beard?" Gwendolyn asked –"because he left with a friend of mine."

The next day Gwendolyn's friend wrote a gloating poem about it. We all sat in a circle on the grass. She gave everyone a Xerox copy. "I wrote this just this morning," she smirked. The poem was called "Green Shoes." She sat cross-legged while she read. Her madras skirt was stretched around both knees, but it wasn't covering her crotch. I was astonished. She wasn't wearing underpants.

A white string showed.

On my second night I sat next to Gwendolyn on a bench for a reading. She had become my best friend. The theater was crowded. "There are no men anywhere," I complained. I was ready to go back to New York. It was comforting to be able to pour my maudlin complaint into Gwendolyn's ear. She listened earnestly.

Suddenly a handsome stranger in a white shirt climbed over the hard wood bench from the row behind us and sat down on my other side.

"Hello, I'm Kazimir Noble," he said. "I'm an artist. They pay me to do nothing."

I was enormously embarrassed. Kazimir Noble. His name alone was too handsome and improbable. "Well, hello and goodbye," Gwendolyn sang in a loud singsong. She was gone.

He had a beauty mark on one ear lobe as if it were pierced for an earring. The lights dimmed. The poet on stage, who was the poetry editor of the New Yorker and had published me four times, announced that his first poem was about a Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam. "Russian was my first language," Kazimir whispered to me.

"Are you Russian?" I asked, surprised, as if I had just opened a book by Turgenev, and he was the hero.

"Yes. But I was born here. I grew up in New Jersey," he said.

His Russian face was both gaunt and voluptuous. His nose was more beautiful even than my father's. He was tall and broad-shouldered. In the middle of the reading I touched his arm to reassure him, to reassure myself that he was real. "Let's leave," Kazimir whispered. We left the theatre rudely. Outside, I was staggered at every step by his beauty.

"How old are you?" I asked.

"Twenty-seven." It seemed almost obscene for him to be that young.

"I'm from New York," I said quickly. "Where do you live?"

"I don't live anywhere."

"Where would you like to live?"

"New York," he said. We kissed in a grove of shadows near the pottery barn. It was like a marriage, like breaking a wineglass in the sight of God. "Do you want to stay with me tonight?" he asked.

"I do," I said.

In the dark, Kazimir undid my dress. He bared one breast. "They're big," he said admiringly, touching me.

"Oh, they change during the course of the month," I confessed, "they get bigger and smaller as the month goes along."

"It's like getting several women at once," he replied. I felt like an Indian goddess covered with breasts. I combed my long dark hair with the fingers of both hands, drawing it out to its full length, and letting it fall around my face.

"Your hair is like a character in a novel," he said, closing me in his arms.

The artists and the writers lived in houses that were far apart. I was going to sleep with him in his room. He came with me first to my room so that I could get a change of clothes for breakfast in the dining hall. "How do you want me to look?" I asked.

"I want you to look well-fucked," he answered. I took it as a promise that I would be.

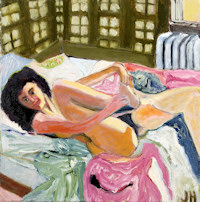

Then we were naked in front of a fire. There was a rainbow Canadian blanket on his bed. I admired his Cyrillic hands and feet, the sweat raining from under his soft brown hair.

His penis like the trunk of a tree.

I went down on him. He seemed impressed. "Jewish girls," he said. He didn't come. I was glad. I wanted him too much. He entered me with one thrust. My legs were bent. I kissed his Adam's apple. "I like the idea of your small feet somewhere around my knees," he said on top of me. He looked like Nureyev, it was a miracle that he wasn't gay. I kissed his neck again and again. I never thought of coming myself. I waited for him to cry out in pleasure. A long prolonged cry, like "Tim-ber!" His silence grew deeper.

There was a forest of silence. He had come.

"Why did you pick me?" I asked the next morning.

"I like your small feet," he said. "If you're unfaithful, I'll cut them off."

I laughed, pleased. I couldn't imagine how I would ever need to be unfaithful to him. I loved everything about him.

"As soon as I saw you," Kazimir said, "I wanted to have a child. I wanted to impregnate you." No man had ever said this to me before. It seemed so primitive a sign of commitment; I was touched. Then I was afraid I would lose him because I couldn't have a child.

"I can't," I confessed.

"Why?"

"I had my tubes severed."

I saw the change along his cheeks. A cloud covered his face.

"I had a son," he admitted. "But I didn't like the mother."

"Oh," I said, relieved. Nature was appeased. He had had a son; he wouldn't have to leave me.

"You'll love my children," I said. I thought they were my chief assets, that I was most desirable in my motherhood, like a coral illustration in Water Babies, of the good fairy, Miss Doasyouwouldbedonetoby, surrounded by little ones with gossamer wings. Summers in Cape Cod, I read this book over and over to Lily but always cried when I came to the part about the otter who had a "sweet obedient husband," because it reminded me of Daniel. Finally Lily grabbed the book away from me. "I can read it faster by myself," she said.

"Do you want to go swimming?" Kazimir asked.

"I have to get my suit."

"You won't need it," he said. I climbed into his tall truck, and we drove to a local waterfall, called Buttermilk Falls. We were the only ones there. We swam naked in shallow water as if we were in paradise. He caught a fish with his bare hands. But then I saw the fish was wounded and dying. Its flailing tail was nearly torn off. He let it go.

Two state troopers arrived. Swimming wasn't allowed. We had to put our clothes on while they watched. I dressed very slowly, my layered skirts sticking to me, wet. The more I hurried, the slower I went, as if I were enjoying putting on a show for the uniformed men. They stood on a rock right above us, their smiles of pleasure clearly visible. They were gawking. It was too early for him to accuse me of immodesty; too soon for me to suspect him of prudery. We left under their watchful gaze, the spell unbroken.

When she was dying, my mother always wrote to me in North Truro, "Stay, don't worry about me, enjoy the last days of Indian Summer," and I did.

One summer, in the back seat of the car, vanilla dripping in the dark, little Ned had announced, biting into the sugar wafer, "It's cone time."

It was cone time for me.

We came to a deserted spot on a road. Kazimir stopped, and unrolled the foam rubber in the bed of the truck. He pulled me down under him. He kissed me with his great closed lips. I wanted him to touch the top of my head with both hands as if he were reading my thoughts in Braille. To enter me. I wanted his penis to penetrate my womb. I wanted, at the moment that my womb would open to receive him, for him to thrust his tongue in my mouth. I wanted to feel as if my womb were splitting open, as if I were Katherine the Great tupping with a bull.

Somehow I couldn't quite get into the right position. Then it was over.

"Slam bam thank you m'am," he said.

Jill Hoffman is the Founding Editor of Mudfish and Mudfish Individual Poet Series. She has a PhD in Literature from Cornell University, an MA from Columbia and a BA from Bennington. Her first book of poems, Mink Coat, was published by Holt, Rinehart & Winston in 1973. Her first novel, Jilted, was published by Simon & Schuster in 1993. She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for Poetry in 1974-1975. She published Black Diaries, poems, with Box Turtle Press in 1990; and The Gates of Pearl, a book-length poem, is forthcoming in 2008/09. She is presently at work on two novels. She lives in New York, and teaches fiction and poetry writing in her home.