Articles

War Jokes Wanted: No Laughing Matter

by Marc Levy and Susan Erony

Colonel:What is that you've got written on your helmet?

Pvt. Joker: Born to Kill, sir.

Colonel:You write "Born to Kill" on your helmet and you wear a peace button.

What's that supposed to be, some kind of sick joke?!

Pvt. Joker: No, sir.

Hasford, Herr, Kubrick: Full Metal Jacket

Picture This

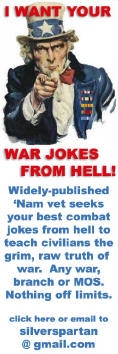

After a time the image and text fell into place. The well known Uncle Sam portrait, stern eyes staring you down, defiant finger stabbing the air, but emblazoned on his left breast, combat ribbons, and above and below him the fiery red phrase "I Want Your War Jokes From Hell!" And beneath this message: "Widely published Nam vet seeks your best combat jokes to teach civilians the grim, raw truth of war. Any war, any branch of service."

The basic assumption: place the ad at VAwatchdog.org, with Armytimes in hard copy, send out informal queries, contact Iraq/Afghanistan veteran associations; the gallows humor will roll in. Larry Scott, web master at VAwatchdog.org even profiled the project: we hoped to write a book on combat jokes with essays on why soldiers resort to dark humor under extreme circumstances. We did not want the puff pieces once gamely trotted out in Humor in Uniform, a monthly Readers Digest collection of old-time military gags which put a smiley face on horror. We sought tasteless, obscene, unforgivable lawless jokes whose wit and irony strips war bare of its mythic bones, looks death full in the face. And laughs. But why did they laugh—those GI jokers?

Veterans who answered the call struggled with the concept of grim war humor. Maybe they didn't get it. Most sent in cute vignettes, sanitized anecdotes, or clean cut bits on inter-service rivalry. In the end we received a half dozen items that conveyed how war numbs the soul and how humor, in service to survival, reflects demonic courage.

Far from the heated stink of carnage, combat vets may tell battle gags to uncomprehending civilians, or to other vets. Or they may set aside the jokes they carried. Misunderstood on the home front, freighted with secret guilt and shame, far from the bullet's madding crowd, gallows humor, may over time, lose its healing cautery.

Public Jester

Nam vet, teacher, and distinguished writer Larry Heinemann, author of Pacos Story (National Book Award), Close Quarters (some say the best fictional account on the Vietnam War) and Black Virgin Mountain, sent this gem:

"A colonel and his sergeant major chopper out to a landing zone to see for themselves the aftermath of a large and bloody firefight. There was heavy fighting, and many casualties on both sides. When they arrive the American KIAs are lined up shoulder to shoulder in back of the makeshift aid station, covered with ponchos and waiting for the choppers to come fetch them. There are many, many bodies. The colonel and the sergeant major slowly make their way down the line, lifting the flaps of the ponchos to view the faces. The colonel looks more and more troubled the farther down the line he goes, and is truly upset. Finally he looks over to the sergeant major and says, "All so young. What a pity. What a waste. Sergeant Major, how old do you think these boys are?" The sergeant major looks at the colonel, and says, "They're all dead, Colonel. That's as old as you get."

Only veterans laughed when the Sergeant Majors Sancho Panza upends his Don Quixote colonel. Instead of sorrow, he cracks a simpleton's smile over a gauntlet of corpses. But the simpleton is no fool. The good Sergeants knife-edge clarity has been won through repeated jousts with mortal danger. His understatement is a moral coup de grace.

Drop Dead Funny

Former Lieutenant Fred Angyo Tomasello Jr., author of Walking Wounded: Memoir of a Combat Veteran, wrote in, "I never thought anyone would want to hear this," then unleashed this tale: "On February 1, 1968, my Marines responded to an attack on the Cam Lo District Headquarters near the Demilitirized Zone. My platoon was tasked with counting the dead and wounded. I assigned the job to Frenchy's fire team. Artillery had butchered the enemy bodies. Heads, many still wearing helmets, were separated from torsos. Arms and legs were scattered all over the battlefield. The NVA had dug shallow trenches under the barbed wire and used sand to try to cover their dead. "Goddamn, they're all fucked up, one of Frenchy's men complains. "They're probably booby trapped too. I ain't touching any dead gooks. Frenchy shoves him in the chest and yells, "What the fuck's wrong with you? You chicken-shit or something? Here! Here's how you do it." Frenchy grabs an ankle sticking up from a shallow trench and tugs as hard as he can. The soldier's body jerks out of the ditch, his other leg flops behind him and the leg that Frenchy's holding snaps from the body. Frenchy holds the leg up at me and smiles. "Hey, Lieutenant, he says, "Lets grab one leg each and make a wish."

Civilians were shocked by the tale. How could well disciplined US troops laugh as they violate enemy losses? And why, forty years later, did combat vets roar at the grisly punch line? Frenchy pokes fun at superstition, at himself; he correctly assumes the Lieutenant will understand. Why is that? Because counting corpses is normal. It has been done many times. War wisdom counsels caution but do the job, Marine, and do it right. Rocket, mortar and sapper attacks, day and night ambushes, hunting and being hunted by other human beings, have bled all mercy from these men. They are numb to gods, immune to devils. They act in league with death, they have become it, which frees them to mock their mirror image.

"Mental survival depended on the ability to view life as a black comedy," said holocaust survivor Thomas Retjo, author of The Reluctant Adventurer. Or as former Lieutenant Tomasello, Jr wrote, "If you don't laugh, you'll cry." In the valleys and shadows of death, hope dies last.

Battle jokes offer a unique insight into how the human psyche preserves itself. To not be overwhelmed, the battlefield joker presides over the nightmare of the dead or frightfully mangled, human beings. With a devil's grin, he defuses chaos. By standing meaning on its head, he erases, for however brief a moment, horror's indelible imprint.

The attentive reader may ask: if few vets submitted jokes, and few these days tell them, why did those who heard the battle antics convulse with laughter? To this we have no answer.

Little Bobby

The following arrived from net friend Tommy Skeins, web master of buffgrunt.com, a site dedicated to all things America, especially 4/3 Light Infantry Brigade, one of several units at My Lai:

"Little Bobby and his 6th grade class were given the assignment of writing a fairy tale with a moral ending. The next day, the teacher first called on Susie, who wrote about not counting your chickens before they're hatched. Then came Mary, whose story involved not crying wolf. Then, it was Little Bobby's turn. 'My uncle Tony was in Vietnam and one time he went on a combat assault,' he said. 'On the way, he drank a case of beer, then jumped off the helicopter and killed 100 Viet Cong. He killed the first 80 with his rifle, 10 with his pistol and clubbed the other 10 to death. After that, he took a knife and a pair of pliers and yanked out all the gold teeth from the dead Viet Cong. The teacher was aghast and blurted out: 'Bobby, that's terrible! Is there any moral in that awful story?" Little Bobby shrugged and said: 'Don't fuck with my uncle Tony when he's been drinking.'"

Bobby's obscene remark falls like a Zen masters enlightened blow to the face. His foul words wield the uncle's malice yet paradoxically shield the boy from horror.

Let The Bad Times Roll

In 1972 Michael Casey wrote Obscenities, which won the Yale Younger Poets Award, and was re-issued by Carnegie-Mellon in 2002. A gem in the book is the poem "A Bummer." In twenty-six stark lines, Casey depicts an encounter between a column of tracks (mechanized vehicles), a peasant farmer, and the TC (track commander). The poem's last mordant lines and final barbed flourish could have been written yesterday, today, or tomorrow.

A Bummer

We were going single file

Through his rice paddies

And the farmer

Started hitting the lead track

With a rake

He wouldn't stop

The TC went to talk to him

And the farmer

Tried to hit him too

So the tracks went sideways

Side by side

Through the guys fields

Instead of single file

Hard On, Proud Mary

Bummer, Wallace, Rosemary's Baby

The Rutgers Road Runner

And

Go Get Em-Done Got Em

Went side by side

Through the fields

If you have a farm in Vietnam

And a house in hell

Sell the farm

And go home.

Such things and worse transpire in combat's ironic cauldron, and will continue, until unwanted American troops, struggling to hold out in foreign lands with dignity, depart. Even then a blood trail of guilt, shame and sorrow will long shadow their lives, and those they love. And that, Mr. Bring' Em On, is no laughing matter.

(Previously published on CounterPunch.org, 27 September 2008))

Marc Levy was an infantry medic with Delta 1/7 First Cavalry in Vietnam and Cambodia in 1970. He can be reached at silverspartan@gmail.com.

Susan Erony is an artist and art historian who has exhibited extensively in Europe and the US. She can be reached at erony1@verizon.net.

Fred Angyo Tomasello's book is available at http://web.mac.com/kbft2929/iWeb/WalkingWounded/Welcome.html.

Larry Scott's VAwatchdog.org profile on War Jokes Wanted is at http://www.vawatchdog.org/08/nf08/nfJUL08/nf070708-1.htm.

Obscenities, by Michael Casey, is available at: http://www.cmu.edu/universitypress/browse/ (poem used by permission of the author)