Reviews

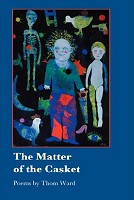

The Matter of the Casket

Poems by Thom Ward

The Matter of the Casket

The Matter of the Casket

Poems by Thom Ward

Custom Words, 2007; 84 pages; $17

ISBN 978-1933456690, Paper

by Donald Zirilli

The Matter of the Casket is subtitled "Poems by Thom Ward," so we know what he thinks they are. One might also call them prose poems or maybe even flash fiction. In other words, they are poems deprived of line breaks. I was disappointed to find this out, because I've been interested of late in line breaks and their notorious side effect, lines. It is the line, after all, that give the reader the sense of verse, or lyric, or song. The poems by Thom Ward suggest none of those things, which begs the question, what do they suggest? Fortunately, there is a ready answer. In all but two cases, they suggest fiction (the two cases suggest essays), and here is where the action lies: the way these poems play with the expectations of fiction.

Once more Night said to the man, Put on this black cap and go sit in

the corner.

All right, said the man, But I won't abandon my lover's initials I've

carved into my wrist.

Better ask Lust permission for that, said Night.

("Carvings")

Prose and its paragraphs are never challenged. It is always genre that is challenged, and Mr. Ward takes advantage of many of the genres available to fiction. Most often he takes on the allegorical fable. Similarly, he will exploit the naivety of traditional storytelling, but more modern fiction styles are also fair game, including conversational first-person, cinematic en media res, theatrical dialog, and immersion into a character's thoughts. And these are just the frameworks. Within them, more styles and genres of prose combine and clash. Perhaps this is why R. D. Pohl of the Buffalo News writes, "all the useful associations I could bring to these pieces required that I read them as fictions."

Take, for example, A Small Business in the Safest Part of Town, which starts "Each night he worried some bad man would break in and steal his best business things." The generalities of "some bad man" and "his best business things" are obvious cues for a fairy tale, and even remind us that the genre is targeted to children. The cues continue to be laid on thick throughout the story. The only counterpoint is the plot itself, which is dark and rewards the ruthless. This is not an unfamiliar tactic, reminiscent of Fractured Fairy Tales, but most of the tales in this book are not so readily parsed.

but the animals were not invited, at least not by me, who had built my ark

with big dollars and rubber bands. Everyone else insisted on hardwood and

pitch but that was old book. A project must stay loose, remain in the black,

otherwise the stories we make up about the world put on sneakers and

sweats, race away from us. Into the hull I stuffed the hundred million breaths

my grandmother took. Didn't matter what rubber bands were employed,

though Grant proved more pliable than Franklin. Makes sense when you

consider the hooch in his gut.

("The Hurricane's Name was Noah")

We don't know why the hurricane is named Noah. Does it suggest Noah's complicity? Is it merely the inspiration for a man to connect to himself to a Biblical story? All we know is that the mere mention of Noah allows for a series of contrasts: no animals this time, no wood this time, etc. This guy makes his boat out of money. A satire of the greedy stockbroker? Perhaps, but what is interesting is not just how the story is different, but also how the prose of corporate marketing infects what would otherwise be a rather working class monologue. The corporate-speak of a personified "project" that must be "in the black" collides with "hooch in the gut." The final sentence, "The children howled as we pushed them up the ramp," belies (transcends?) both white and blue collars, suggesting more story just as the story ends, and leaving us with a disturbing new resonance.

My personal favorites are the poems that go completely overboard, where the story becomes impossible to follow. All we have are some images, players if you will, resonant with themes, that look for all the world like they are in a story, but all the story has been shaken out of it. If I'm confusing you, the first sentence of Unwellness should clear it up: "Sensing a bout of unwellness Pill took a woman." The rest of the story does not try to make sense of this strange reversal, but rather plunges eagerly into its impossibility. It is a case of classic Surrealism, in my humble opinion, with an important point: the idea of "taking a pill" is a societal or cultural construct inseparable from language. By switching around the language a bit, Mr. Ward demonstrates just how much the reality of pill-taking derives from language alone, some of which has been created by advertising and marketing departments. When such an expose is done in a poem, I find it particularly satisfying, since poetry is also a trick of language. It's like a magician working with a glass hat.

Because there is so much digestible prose in this work, even if it is so often skewed, I can justifiably claim it to be more accessible than many other books of poetry. However, a full appreciation of the work does demand a careful, cognizant reading. As a whole, I could not find strong unifying themes, despite its framing poems, which stand separate from the three-part structure of the book, the intro being a tale of the afterlife, the outro being a tale of a funeral (a more mundane sort of afterlife). Death or its concerns do not seem to dominate the stories in between. Nor can I discern a reason for the three sections, except to break things up. Form, instead of theme, unifies the book. I recommend the book simply for the pleasure of seeing the myriad ways a poet can transform prose.

Perhaps The Matter of the Casket is not a matter of death at all, or not exclusively. Perhaps the title points to the meaning that lies in the coffin known as language. Is he saying that meaning is already dead, or by revealing the artifice is he intent on its resurrection? I would suggest a little of both.

Donald Zirilli has a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Drew University. He has been writing poetry for over twenty years, with publications in The River, Art Times, The Panhandler and Grasslands Review. His chapbook "My History of Mental Illness," was published by Lopside Press in 2007. He is the co-editor of Now Culture and the art editor of Shit Creek Review.

Four Poems from The Matter of the Casket

Gates

So is this the gate? said the man to what he assumed

to be an angel who stood before a barrier not known to

earth. It resembled a thick yet translucent column of wax.

There are many gates, said the angel.

I mean the gate, the one I worked to achieve in my life, the

one that proves I did more help than hurt.

There are many gates, said the angel. How easily an adoring

crowd becomes a vindictive mob, how quickly a beam of light

twists into shadow.

I don't understand, said the man.

Your task is to discover what shape you are, said the angel.

Then you will know where to find and how to pass through the gates.

But I'm already dead, cried the man. I have no shape.

Death has a host of shapes to be discovered, said the angel.

Others have.

This is all so confusing, said the man. What about pearly,

and that eye of the needle and camel thing? We were told those

are the clues.

Do not panic. Time is no longer an issue, said the angel.

And remember, there are many gates.

Schadenfreude

There's no delight in standing behind my metal cart, the tedious wait

to hand over coupons, a few bills to the cashier. But to

browse The Enquirer, learn that the government's Secret Alligator Man

demolished the laboratory, mauled a biologist, then scurried to the

swamps, perhaps at this moment floats surreptitiously toward a

pontoon full of lawyers, their amethyst wives, makes for a perverse, if

only brief, satisfaction.

Like the humid summer evening in the park, bullheaded Patty Minx

kicked the winning goal into the net for the opposing team; the day

Bob Tankenburg, fast to boast about his Porsche, was nabbed doing

seventy-six down Main, his license on the bureau

by his bed. When the Baptists' proposal for a new church was

bounced, Presbyterian elders chuckled to themselves, launched

an impromptu membership drive.

Some repudiate schadenfreude, say it doesn't exist, or if it does, only

in the grumblings of the cynic, the misanthrope. But we know better,

realize how it whirlpools our coffee, stains our tongues — the cold,

blunt smile upon learning the obnoxious brat five doors down has

been suspended from school; the black, bright tickle we feel, as

retrieving the mail from our box we notice the lazy neighbor's mutt

has left a pyramid of shit, still steaming, still warm — O praise this

eighth wonder of the world, this impeccable, perfect offering — on

the meticulous neighbor's lawn.

Family Skeleton

One bone at a time, Florence gave her dog the family skeleton.

It's pointless to keep it in the closet, she told her

septuagenarian friends over tea.

I think Wallace knows it's invaluable; that's why he takes

such care with each bone.

The women nodded in agreement, secretly wishing they had

thought of this clever, canine solution.

Yes, come to think of it, my pooch is gutsier than any cat,

said Helen.

Meanwhile, in the sunny part of the yard Florence's dog

continued to rearrange the family bones: MEDICATE THE

SKELETON SAVE ME FROM MYSELF were the

first messages he spread out in the grass . . ..

Of Rocks

When do rocks get to retire? Geologists report wind and water action

over millions of years reduces boulders to pebbles, and it's hard

to disagree with that. But isn't there a point when rocks don't have to

punctuate mountains, reinforce lakes, contribute to the geological GNP?

As with octogenarians do they ever get to eat dessert first, take

spontaneous naps? The Bible, which often illuminates, or, at least

parables, is of little help. Simon Peter, whom our Lord named Rock,

didn't get to enjoy his retirement — no shuffleboard or golf for him.

In this common era, we have unions. Still, is there ever a day when

an outcrop gets a coffee break? I empathize with rocks, being mortals

like us, aging painfully, shingles and arthritis, yet without the safety net of

Social Security. Perhaps in the Sea of Galilee it wasn't fish Simon and his

pals were trying to snare, but rocks, smooth to the touch, void of

tongues, modest and reliable. Rocks, here before and here after, quietly

doing their innocuous rock things, never yearning for prophets or

messiahs.