Articles

The Imagination and the Psyche

by Elaine Schwager

Creative Imagination and the 'Inspirational Other':

The 'Dramatis Personae' of Writing

by Victor L. Schermer

Ten Mile Meadow: A Conservatory

of Land and Language (with photos)

~ . ~ . ~

The Imagination and the Psyche

by Elaine Schwager

There is a dark

inscrutable workmanship that reconciles

Discordant elements, makes them cling together

In one society.

-- William Wordsworth

Imagination is the power to see what cannot be seen by the five senses and to make connections that are not yet there. One imagines or discerns what is not conventionally "seen" in the present, what may come, and what was. It is thus an element of intuition, memory as well as "vision" or prophecy. Paradoxically, while thought of as that which is in opposition to the "real" or scientific, the discovery of facts, imagination is that by which we intuit or "sense" what is more "objective" or real than the "real."

Imagination reaches for what is beyond appearance, an intelligence beyond the self. Einstein said imagination is more important than knowledge, William Carlos Williams said that it was the one reality in an unreal world, and Coleridge (1997) viewed the poet as one "who brings the whole soul of man into activity . . . by that synthetic and magical power to which we have designated the name 'imagination'." This is similar to Keats declaring: "Call the world, if you please, the vale of soul-making. Then you will find out the use of the world." In this sense, imagination, whether through poetry (art) or science is that which keeps trying to bring the "realer" into the less real world. Einstein's science imagined a reality that was not part of our present reality, yet 'there,' waiting for the imagination to discern. Poetry, as Williams, Coleridge and Keats describe, attempts to manifest the intelligence and reality of the soul, to expand the conscious mind of the poet and others.

The thoroughgoing integration of what philosophy discriminates

as subject and object is the characteristic of every work of art.

The completeness of the integration is the measure of its esthetic status.

-- John Dewey

Imagination might be thought of as a sixth sense that intuits the presence of reality that has not yet been manifested or put into form or image. The quality of our imaginative or the creative manifestation of our imagination is based on the emotional and spiritual development of our own subjectivity. Our past may be constantly revised in relation to the development of our capacity for compassion, the present more fully engaged to the extent we are able to free ourselves of negative past determinants and cleanse ourselves of limited and prejudicial perceptions, the future more clearly ‘seen' or prophesied to the extent we are in harmony with the order of the universe. The aesthetic value of imagination's manifestation is thus to some extent related to the development of consciousness. A spider can create a beautiful web by instinct. It is not an act of consciousness or imagination.

The imagination can be dually motivated, to both create and destroy, but its most elevated use is to transcend duality. John Dewey said of the use of imagination in art: "The thoroughgoing integration of what philosophy discriminates as subject and object is the characteristic of every work of art. The completeness of the integration is the measure of its esthetic status."

a bridge, to transform fantasies, dreams

intuitions and desires into reality

Imagination can serve healing and the elevation of the self to higher forms of integration and moral functioning or ingeniously invent to harm and destroy. It can brilliantly reveal truth or cunningly lie. It has both aesthetic and problem-solving capacities which can be manifested through art or science to create beauty and harmony, which gives one a sense of connection to what is good, meaningful and makes sense in life. It can dissolve or heal pain, unhappiness or suffering, it can or create pain, unhappiness or suffering. It in itself is a powerful, amoral force dependent on the moral and spiritual development of the self for how it manifests itself, that is, what kind of images it will produce to reveal what has not yet been revealed.

Imagination, whether operating in relationships, science, art, or spirituality, acts as a bridge, to transform fantasies, dreams, intuitions and desires into reality. The world that is is the world that was imagined, the past. Imagination serves to transcend the way existent objectivity defines subjectivity and to establish new relations between the subjective and objective. Whether through dreams, art, the spontaneous flow of silence in meditation, creative endeavors or involvement in living we are imagined as well as imagining.

Imagination's aesthetic value and power depends on the freedom to move reflectively between the polarities of subjectivity and objectivity as well as between polarities within the self. Imagination is essentially the capacity to know experientially, through partaking in the transformative capacity of mind, the simultaneous feeling of impermanence in everything, the eternal nature of the transcendent capacity of which it is a human link and the joy and power of the creative which is its manifestation. It defies a method derived from logical science, geared to learn about and gain control of the external world, to penetrate the depths, mystery and contradictions of one's innermost self.

. . . constitutive to man, stemming from

a need to regain spontaneity and freedom

Pursuits of imagination have been represented mythologically in symbols of flight, exemplifying freedom and transcendence and quests of the hero who pursues journeys on the edge or in the interface of what can be known and what is mysterious and never fully known. These 'instincts' of imagination and transcendence are believed to be 'constitutive to man,' stemming from a need to "regain spontaneity and freedom." (Eliade, p. 108). They are equally as objective as instincts for food, sex, survival and to relate to others and also make their demands on the mind. They can be subject to dissociation and repression and, when engaged and recognized, become an underlying motivational force for other instincts and feelings.

Current scientific enterprises are asserting basic transcendent, creative and imaginative forces in life and a continuity of intelligence and energy among human, natural and even possibly inanimate forms. These ideas are providing evidence in scientific and mathematical notation to support experiences mystics and artists have intuited for centuries. William James (1902, 1936) defines 'mystical' as a state of rapture and form of consciousness which provides insight not available to the discursive intellect. Imagination may be thought of as necessary aspect of that form of consciousness which provides that leap beyond the discursive intellect into the realm of the transcendent.

mysticism . . . taking subjectivity to its limits

to encounter a reality more profound

Bertrand Russell (1957) raises the question as to whether there are two ways of knowing: intuition, representing the mystical way of knowing, and reason, representing logic. Mysticism may be viewed as taking one's subjectivity to its limits to encounter a reality perhaps more profound. Russell believes that what distinguishes mystical knowing from logical or analytic knowing is a belief in insight or revelation as achieving a penetrating reach for wisdom rather than through a science relying on the senses. Mystics believe they have penetrated to a knowledge of a reality behind appearance. Mystical knowledge also does not admit opposites or division, denies the reality of time, sees evil as illusory and a function of a false division of reality. The insights of this type of knowledge are often difficult to integrate into a world dominated by divided consciousness, which functions in time and manifests the brutality and violence that stem from unintegrated consciousness. Those who achieve these insights thus often either withdraw from the world, believing it subject-dependent and therefore illusory, find in art an expression of this unity or wholeness or who teach by example.

[imagination,] a corrosive operation that is

practiced on the real, an operation aimed not at evading

but at transcending reality . . . -- Jean-Paul Sartre

Contact with the transcendent offers an opportunity for diminished suffering as a result of increased clarity, deepened understanding and an intuitive integration of dualities that contribute to the constant state of dilemma that causes unhappiness and pain. In this sense, as the personality matures and integrates by virtue of the transcendent function, feelings and perceptions become more clarified and less dominantly repetitions of the past.

The ongoing symbolic transformation of consciousness via the imagination is central to the transcendent function. Sartre (1963) sees imagination as "a corrosive operation that is practiced on the real, an operation aimed not at evading but at transcending reality . . ." (p.22). Imagination is not memory or fantasy, but a way of establishing a relationship to these that is meaningful, freeing one from the pull of both towards repetition, victimization, or helplessness, that is, modes of suffering. A focus on understanding the present and suffering in terms of the past may shortchange the role imagination plays as a route towards transcendence and liberation from suffering.

Imagination has its own developmental progression and amalgam of qualities, including the capacity to symbolize, play with new relationships, the capacity for intense concentration, to be alone, to doubt and integrate opposites or polarities within the self--all of which increase inner freedom.

Dogma, caprice . . . derivatives of trauma

. . . potentially duplicate . . . 'soul murder'. . . .

[imagination] intertwines spirituality and creativity

Dogma, caprice, arbitrariness or rigidity in response to another are derivatives of trauma that cripple imagination and create oppressive inter-subjective environments rather than liberating ones. They potentially duplicate the situation Shengold (1989) describes as 'soul murder.' He showed the negative effects of children's thoughts and feelings being distorted or suppressed by "knowing" adults. While optimal recognition of the imaginative aspect of self--nurturing and giving it freedom--is more likely to give it opportunity to flower, it paradoxically may defy all expectation.

History has shown that imagination sometimes brings forth its most magnificent manifestations in the face of parental loss, rejection, poverty, imprisonment, and political oppression. The origin, and force of imagination, how it transforms adversity and oppression is ultimately mysterious. It resists reduction to explanation or formulas for its cultivation or unfolding, yet its presence in meaningful lives and the progress of civilization is evident. It is in some way that which intertwines spirituality and creativity: A force straining to contact the eternal, aspiring to transcend dogma, personal gods and wishes and to approach life "unarmed" without preconceptions.

erasure of [the artist's personality]

to reach something more universal

The artist, as well as the scientist seeks a more objective reality beyond the manifest. Art is not merely an expression of ephemeral feelings or of the personality of the artist, but rather, the erasure or use of them to reach something more existent and universal. The striving for objectivity that is part of art and poetics, was expressed by Rilke (1985) when he said of Cezanne's work that he "understood that to burden a work of art with any ulterior motive, to impress it with one's hopes or wishes, is to weaken it and lay an obstacle in the path of pure achievement" (P.xvii). Rank (1989) saw the artist and the spiritual seeker reaching for the eternal. In the domain of science Einstein saw the untangling of the "great eternal riddle" out there as a liberation from the "merely personal," a road paralleling that to "religious paradise" (Schlipp 1951). Imagination is thus both the intelligence and the medium by which scientists and artists seek to manifest this greater intelligence.

the superior scope of mystic intuition

and sheer faith as paths toward understanding

Science is often thought of as being in opposition to imagination or that which holds imagination in check through its emphasis on empirical and rational approaches and by examining the external world systematically. Science grew in large part as a revolt against the Middle Ages notion that truth resides as well in the limitless invisible realm rather than just in demonstrable reality, and its consequent ideas of magic, faith and mysticism. As early as 1270, Thomas Aquinas expressed grave concern over the limitations of a science-oriented rationalism and what can be discerned by the senses. He believed in "the superior scope of mystic intuition and sheer faith as paths toward understanding" (Goldstein, 1995 p. 250).

the gold sought in alchemy: a golden state of mind

The 16th century saw a revival of occult sciences, which Aristotelianism had kept at bay. "Hermetic" wisdom viewed knowledge as the "union of subject and object, in a psychic-emotional identification with images rather than a purely intellectual examination of concepts." (Berman, 1981 p. 73). The gold sought in alchemy was a "golden" state of mind, the altered state of consciousness which overwhelms the person in an experience such as the Zen satori or the God-experience recorded by such Western mystics as Jacob Boehme (himself an alchemist), St. John of the Cross, or St. Theresa Of Avila. Alchemy is thought to be the last major attempt to synthesize human consciousness in the West. Jung saw alchemists as the psychologists of their day searching for the philosopher's stone, the mysterious lapis that symbolized the total man, that is an integration of human knowledge that would give evidence of transcendental and meaningful aspects of the psyche.

Jung believed that rejection of alchemy by the Scientific Revolution resulted in a repression that had tragic consequences--including genocide, barbarism and increasing mental illness. It meant not facing our shadow or demon side, which was the essence of alchemy's journey. The consequence of this was the creation of the technology needed to effect genocide and human annihilation. The alchemical integration was:

. . . a constant process of seething and generating, it never allows life to come to a rest; it endlessly promotes evolution and development and is always in opposition to standstill and the established order of things. Yet through its one-side preponderance, one would lose the ground of reality under one's feet and become oblivious to earthly limitations. The person who loses contact with his instinct nature is subject to psychological inflation. (Whitmont, 1991, pg. 89).

To the alchemist, material events and psychic process were equivalent: The alchemist did not confront matter, but rather, permeated it. There was not an unconscious or symbolism because everything was symbolic and conscious. There was belief in a way of knowing behind phenomenal appearances, that involved obliteration of the subject/object distinction, and diminution of the ego.

imagination, a force of scientific discovery

While since the 17th century, reason has been sovereign and Darwin's Theory of Evolution was the influential science of the day, modern science seems to be confirming through its methods the centrality of imagination and creativity as both forces in the universe and forces of discovery.

Progress, according to Kuhn (1962, 1996) and Feyerabend (1993) depends not only on dialectic but also on the emergence of anomalous configurations. Unforeseen paradigms can revolutionize the existing sense of order, not merely modify it by incremental, accumulative bit-by-bit additions of knowledge. These new paradigms are born of imagination and often arise out of a crisis, a sense that an existing order or paradigm cannot account for certain problems, data or experience.

when one paradigm replaces another,

scientists work in a different world

Kuhn's ideas about scientific revolutions stress the dramatic, noncontinuous, often cataclysmic nature of scientific change, which raised anxiety among philosophers of science because of its implications of irrationality. Kuhn viewed scientific revolution as involving a total change in standards and methods, so that rational, external evaluation of competing views appears impossible. He said when one theory or "paradigm replaces another, scientists work in a different world" (Thagard 1992 p. 4).

Complexity theory in contrast with traditional reductionism is concerned with "emergence." This idea implies that at each new level of nature, laws which apply at lower levels may be irrelevant. The Belgian scientist Ilya Prigogine was concerned with nature as becoming as well with nature as being. He found perturbations of physical systems that were unpredictable and that would cause the whole system to move to a higher state of order than the former state. He was interested in non-linear systems that could generate novel kinds of order, which because of its origins in non-linear feedback, is impossible to predict or control. Prigogine says science is

heading towards a new synthesis, a new naturalism. Perhaps we will eventually be able to combine the western tradition, with its emphasis on experimentation and quantitative formulations, with a tradition such as the Chinese one, with its view of a spontaneous self-organizing world (Prigogine and Stengers (1984) p. 22).

Of matter he says:

Matter is no longer the passive substance described in the mechanistic world view but is associated with spontaneous activity. This change is so profound...that we can really speak about a new dialogue of man and nature. (Prigognine and Stengers p. 9)

Complexity and Chaos theory are thought by many to lower the status man gained as a result of Darwin's evolutionary theory. Rather than seeing man as at the pinnacle of evolution, complexity theory tends to see humanity and nature as together in one big complex adaptive system.

Loss of certainty in progress reigns supreme.

A Great Leveling takes place, in which the pretensions both of science (to uncover nature) and of society (to push ahead) are dismissed as utopian dreams. Loss of certainty in progress reigns supreme. It is not only the outcome of complexity and chaos theories, but their unconscious inspiration (Guillott and Kumar, 1997 p.188).

Bohm's (1980) implicate order includes his vision of the cosmos as a hologram, where each part of the universe contains or enfolds the whole, allowing for the creation of separate but related events, outside of causality. He also states "that as the implicate order unfolds to manifest the moment-to-moment reality of the explicate order, new 'creative' patterns tend to emerge. These matters are expressions of a creative and imaginative urge in the deepest implicate aspect of the cosmos."

a force which operates like a trickster

to upset the applecart of reality . . .

in art or poetry . . . a muse

One might say there is an objective process in which one participates by means of the imagination, a force which operates much like a trickster to continually upset the apple cart of reality. The trickster often figures centrally in creation myths as a paradoxical character, full of irreverent vitality, who creates life in ingenuous ways, often disturbing conventions, and preconceptions. He is in some way the archetype of the imagination or world maker, associated with the light of consciousness or bringer or stealer of fire. He can pop up anywhere and makes the world in which he moves. In this way, the Archetype trickster or Imagination gives immunity to the oppression of the present and may be our most effective way of creating a stake in the future. It is a revolutionary force in creative endeavors and breaks new ground in relationships. In art or poetry it may be called a muse.

What Adrienne Rich (1993) says of poetry may also be said of the imagination.

Poetry is not a resting on the given, but a questing toward what might otherwise be. It will always pick a quarrel with the found place, the refuge, the sanctuary, the revolution that is losing momentum . . . poetry will go on harassing the poet until, and unless, it is driven away (p.234).

(A practicing psychotherapist and respected poet, Elaine Schwager's latest collection is I Want Your Chair (Rattapallax, 2000) (See Reviews, Jan 2001). The present article formalizes some of the insights she conveyed in a two-part interview which appeared in the Jan/Feb 2001 issues.)

___

References cited:

Berman, C.(1981) The Re-enchantment of the World. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Bohm, D.(1980) Wholeness and the Implicate Order. (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

Coleridge, S. (1817) Biographia Literaria. In Coleridge, Poems and Prose ed. P. Washington, pp. 227-237 (NY, Everyman's Library, Knopf)

Eliade, M.(1975) Myths, Dreams and Mysteries (NY, Harper and Row)

Feyerabend, P. (1993) Against Method (London:Verso)

Gillott, J. and Kumar, M.(1997) Science and the Retreat From Reason. (NY, Monthly Review Press)

Goldstein, T. (1995) Dawn of Modern Science (NY, Da capo Press)

Inglis, F. (1969) Keats (NY, Arco)

James, W. (1902,1936) The Varieties of Religious Experience (NY, The Modern Library)

Kuhn,T (1996). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. (Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Press)

Prigogine and Stengers (1984) Order Out of Chaos (London, Fontana)

Rank, O. (1989) Art and the Artist (NY, W.W. Norton & Co.)

Rilke, R.M. (1985) Letter on Cezanne (NY, Fromm International Publishing Corp.)

Rich, A. (1993) What is found there (NY, Norton)

Russell, B. (1957) Mysticism and Logic (NY, Doubleday Anchor)

Sartre, J.P.(1963) Saint Genet (NY, Mentor Books)

Schlipp P.A. ed. (1951) Albert Einstein, Philosopher Scientist N.Y.

Shengold, L. (1989), Soul Murder, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Thagard, P (1992) Conceptual Revolutions. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Whitmont, E. (1991) Psyche and Substance Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Williams, W.C. (1978) A Recognizable Image: William Carlos Williams on Art and Artists (ed. and introduction by Bram Pijkstra) New York: New Directions.

~ . ~

Article

Creative Imagination and the 'Inspirational Other':

The 'Dramatis Personae' of Writing

by Victor L. Schermer

I am a psychoanalytic psychologist who also happens to be a lover of poetry. I have been fortunate enough to have known personally some fine contemporary poets such as Stephen Berg, Michael Graves, Jeff Marx, and Elaine Schwager, but claim no real expertise on the subject. My credentials are simply and humbly an abiding interest in poetry and poets. Until recently, poetry was for me an avocation that bore no relevance to my chosen profession of psychotherapy, which I had viewed as a self-contained discipline within the framework of the natural and social sciences.

Gradually, however, the "softer," humanistic, literary, and even mystical aspects of therapy became apparent to me. I am sure that this change is as much due to the course of my life as it is to developments within depth psychology. I had undergone a personal trauma, and mid-life crept upon me with its vision of the inevitable ending, leading me to turn inward towards my own subjectivity and search for meaning. Further, traditional psychoanalysis began to admit more of the literary and humanistic side into its inner circles, with the influence especially of the French analysts and intellectuals, such as Andre Green, Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and Jacques Derrida.

Within those evolving personal and professional contexts, I have come to think that psychoanalysis and poetry can have a meeting of the minds and even possess a common "aesthetic," insofar as both seek deep interpretations of human experience and--at their best--can manifest an elegance of technique, perhaps one of the most sensitive and poignant therapeutic examples being that of the Swiss psychiatrist, Sechahaye, who established trust and symbolic capacity within a severely regressed and withdrawn schizophrenic girl by giving her an apple as a token of the mother's nurturing breast. This, for me, is poetry in motion on the brink of real human agony.

. . . poetry as an intersubjective process, the result both

of the interplay of "subselves" within the poet and . . .

Just as psychoanalysis is the result of the interplay of subjectivities (in particular, those of the analyst, the patient, and, as Tom Ogden says, an "Analytic Third," a "super" subject which develops out of the interaction itself), so I have come to see poetry as an intersubjective process, the result both of the interplay of "subselves" within the poet, and of the relationship between a poem, the sources of its creation, other poems and texts, and above all its readers. They are indeed the ones who, by their interest or lack thereof, either bring the poem to life and commend it to future generations or else condemn it to "bloom unseen, and waste its fragrance on the summer air." When T.S. Eliot died, Ezra Pound was asked what could be done to honor him. He said simply, "Read him!" A plain but essential encomium indeed.

all experience . . . the result of the

commingling of consciousnesses

The current psychoanalytic interest in "intersubjectivity" of such forward-looking analysts as Robert Stolorow, Daniel Stern, Jessica Benjamin, and others calls attention to the fact that all experience, rather than emerging from a single, solitary self, is the result of the commingling of consciousnesses. Since humans are inherently social beings, it is something of an illusion that any thought, feeling, or creative act is the product of a lone self autonomously perceiving and conceiving.

Of course, some illusions are necessary, and no one can fault the poet who feels himself, at the moment of gestation, to be alone, "silent, as on a peak in Darien." This notion of the individual standing in solitude apart from the crowd is the culmination of the romantic and modern periods, in which Western man, with great struggle, came to realize his full individuality, but sadly, at the cost of losing some of his connectedness to the human group.

ego: a necessary illusion which diminishes upon an

understanding of the hegemony of the unconscious

The French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan and others have held that the conscious self-determining ego is a necessary illusion which diminishes upon an understanding of the hegemony of the unconscious. Freud, in his early writing recognized that dreams contain "dramatis personae" which represent the subselves of the dreamer. The poet James Wright held that poems are "carefully dreamed." Within this "dream" state, dissociated from conventional discourse, the creative writer forges a text out of the many subselves within. Intersubjectivity adds to this understanding the awareness of the creative, constructivist interaction between the writer and the reader; that what is written fosters a mysterious nexus between selves, others, and a surrounding ineffable "Other," paralleling the "Analytic Third," which offers a powerful context for shared experience.

Artistic creation is an ongoing dynamic and cultural process which we can imagine was "birthed" in the pre-history of mankind in our ancestor's urgent utterances, scribbling of messages, carving of images, and forming architectural structures, which for us remain cryptic in their origins, yet which may ultimately be given to the world as a sacred, and often sacrificial, offering.

we naively read a poem as if

the poet himself were speaking to us

Let me elaborate a bit on the complex inner and outer "dramatis personae" who participate in the making of a poem. I consider the major "players" to be the Persona (the speaker) of the poem; the poet's inspirer or Muse, and the Reader, as much a creation of the poet as he is the real audience, interpreter, and critic.

From the standpoint of our immediate experience, or "phenomenology," we naively read a poem as if the poet himself were speaking to us. However, we may soon discover that the "Persona," the "speaker," is not the poet, but a fictive someone whose "personality" is part of the semiotic of the poem, as much its vehicle as the meter, rhyme, metaphor, metonymy, and meanings of the lines. It can be quite jarring, in fact, to hear a poet read his own poems, because we can well assume that the last individual he had in mind as the "speaker" was his own self in all its actuality. Instead, the poem may hopefully reflect a more universal, "true self". (I am not enough of a postmodernist to give up the belief in an abiding "truth" of our being.)

The speaker of a poem is often a combination of an ideal "orator" (for a particular style or metier) and a "character" the poet has made to speak the lines. For Walt Whitman, for example, even in "Song of Myself", the speaking--nay, singing--Persona is a unique, miraculous, and self-actualizing being. I know of no biographical anecdote of the "real" Whitman walking down the street extolling himself!

Whitman's lonely Persona adopted by many . . .

Within that archetype, however, one also can "hear" a solitary, even lonely, man, haunted by grief, for example, in "Sea Drift" and, monumentally, in "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd". It is this lonely Persona of Whitman's which, in stark relief, evolved into the personae of many a modern American poet. In Wright's collections "The Branch Will Not Break" and "Shall We Gather at the River?" the speaker's persona speaks nobly, like Sappho, in the "pure, clear word," yet is often a debased, suffering outcast trying to find a vestige of redemption for himself and his "wasted" life, as in "Lying on a Hammock on William Duffy's Farm" or "As I Step Over a Puddle in the midst of winter, I Think of an Ancient Chinese Governor."

The poet's Persona powerfully defines the poems. In Shakespeare's sonnets, the speaker is a lover trying to come to grips with the essences of relationship. In E.E. Cummings's poems the de-capitalized (decapitated, castrated?) "i" is a self freed of convention and morbid introspection. In T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land," the speaker, like Teiresias, changes sex and identity. In "The Four Quartets," the (multiple) speakers shift from gods to pedantic professors to dissociated subselves, to frail humans wandering through spaces and places. There are even suggestions in the Quartets that the speaker could be a house or a street or even a memory as such.

harmonies and counterpoints of subselves

. . . within the poem and the reader's own unconscious

The academic's perennial search for symbolic equations, allusions, and meanings in Eliot's poems (as has also been done to death with James Joyce's "Ulysses" and "Finnegan's Wake") obscures the inherent synchronic harmonies and diachronic counterpoints of subselves which can be recognized by the reader to emanate from within the poem and the reader's own unconscious. Travelling now in Ireland, I am hearing Joyce--as well as some lovely, haunting Gaelic--spoken all around me. I pause at W.B. Yeats's grave in Sligo, and see on the stone the lines "Look coldly, on life, on death./Horseman, pass by!" I hear a funeral dirge within my own soul. No one avoids the Horseman, except perhaps in the spirit with which he approaches death. Much, I am afraid, is lost when we read Yeats, Eliot, or Joyce as if trying to decode obscure references to mythology, etc. We lose touch with the music that is "inside" the writing and ourselves.

Turning attention from the personae of the poem to its "Muse," the inspirer and giver of the poem (who is sometimes bizarrely portrayed as an angel sitting on the poet's shoulder whispering the lines!), we find an equally complex interaction of subselves. Tom Stoppard's screenplay for Shakespeare in Love fictionally portrays the Bard seeking the libido he needs to make more plays by finding a real lover (in the film, a woman, although the sonnets suggest that his Muse was a man). In fact, Shakespeare's Muse was not a single person but a concatenation of intimate friends and/or lovers, the inspiration of Hollinghead's "Chronicles," the actors of his day, and the teeming humanity that emerged half-naked in the free-wheeling commerce of the Renaissance.

merit in having a "shadow" or "adversarial"

Muse . . . demon one and the same

Wright, in "Goodbye to the Poetry of Calcium," portrays his Muse, now become tiresome, as a mother whose breast has become dry, and seeks a new muse in a blindness of eyes that have become ashes. Emily Dickinson's Muse often consisted of a psychic "twin" ("I'm a nobody/ Are you a nobody too?"), or, paradoxically, the vapid inhabitants of a culture she knew could never understand her. There is merit in having such a "shadow" or "adversarial" Muse to act as a challenge to the poet. For Rimbaud, the muse was virtually the devil himself, whom he courted with the speech of a lover. The psychoanalyst, Helmuth Kaiser, who escaped from Nazi Germany to Spain and then Topeka, Kansas, once said that his analyst was Hitler (!), one supposes because such a demonic dictator made him aware of his own dark side, while challenging him to save his life. Creative writers know that their Muses and their demons are often one and the same.

In addition to the "Persona" and the "Muse," the (alleged) "Reader" is a member of the cast of writing. The "Reader" of a short story or novel is sometimes addressed directly, usually as a curious and compassionate listener or confidant. Many writers and performing artists court their readers in their writing, yet express "off stage" a certain contempt for them, regarding them as ignorant and unreceptive, as T.S. Eliot wrote, quoting Baudelaire, "Hypocrite, mon sembable, mon frère," ("my likeness, my brother").

as if pushing the limits of the region

where mentor, beloved and demons merge . . .

The "Reader" is a compatriot, a sibling, but somehow beneath the "Writer." The "Reader" can also be a "Savage" (Moby Dick), passionate but in need of education, or, more affectionately, a close friend (as in some of John Berryman's poems.) One of Stephen Berg's recent chapbooks, Porno Diva Numero Uno, consists entirely of a fictional dialogue with the artist, Marcel Duchamp. It is as if Berg were pushing the limits of the region where the mentor, the Reader, the Muse, the beloved, and the disturbing demons merge. In several of Elaine Schwager's poems, the "Reader" is a family member with whom she is seeking a healing connection. In one of her poems, the Persona is a patient who talks in childlike allusions and images, while the Reader, the therapist, stands above him as would a judging parent or a controlling social system. Michael Graves sometimes addresses his poems to a mother-figure who in his mind merges not so much with the Virgin Mary, as with Christ. The power of Graves's poems derives in part from the Teireisas-like bisexual condensation of holy Mother and Son. Graves's trinity is sometimes completed with references to a debauched and bitter father. Graves's poems in this sense become a prayer, a supplication both to a tarnished Trinity, and to the God of Job, who has failed to fulfill His promises.

neither scribe nor creator . . . a conjurer

who stimulates the reader . . . to feel that

his own memories are present in the poem

The Muse no more dictates to the poet what he writes (what poet does not treasure his freedom to create?) than does the poet himself have the final word as to what he scribbles on a sheet of paper. We are so fixated on the concrete presence of the written text, that we neglect to see that the poet is neither a scribe nor a creator sui generis, but rather a conjurer who stimulates the mind of the reader, not merely to interpret, but literally to construct the poetry that the poem merely suggests is there. It is the "negative capability" (Keats) of the poet which not only allows him to see beyond the obvious, but also to omit many details, so that the whole poem becomes merely a metaphor in the reader's mind for what the latter brings to it. Filling in all the blanks will destroy any poem. In achieving poetic grace, the power of omission is greater than the power of commission, leading the entranced and enmeshed reader to feel--correctly, I think--that his own mental associations, memories, and connotations are actually present in the poem itself.

my own multiple selves into relationship

with those of my patient

To conclude by returning to my own craft of psychotherapy (strictly speaking, it becomes truly a craft only at its most fine-tuned moments): the intersubjective perspective has led me as a therapist towards both greater humility, and, paradoxically, greater empowerment. I am ever more humbly aware of the power of the patient to impact upon my own seemingly stoical and detached observer's stance, and at the same time am freed to bring my own multiple selves into relationship with those of my patient. Is it too much to suggest that the poet's craft may be similarly enriched by an awareness of his own multiplicity and the subtle dialogue he is having with readers who are simultaneously the creation of his imagination and the real persons who will have to come to terms, in one way or another, with his curiously stimulating utterings and scribblings? Should he not seek, in his adventures, not only themes and styles and words, but also the many "subjectivities," both sentient and imaginary, which go into the making of a poem?

(Vic Schermer reviews music and literature and conducts frequent interviews. A psychologist in private practice and clinic settings in Philadelphia, he has explored artistic consciousness in professional articles and presented papers on Eliot, Wright, and Dickinson respectively for the Phoenix Reading Series in New York. His poetry has appeared in Rattapallax (Vol. 1, No. 1) and his work appears in this magazine's Big City, Little section (Philadelphia). vlscher@voicenet.com.)

~ . ~

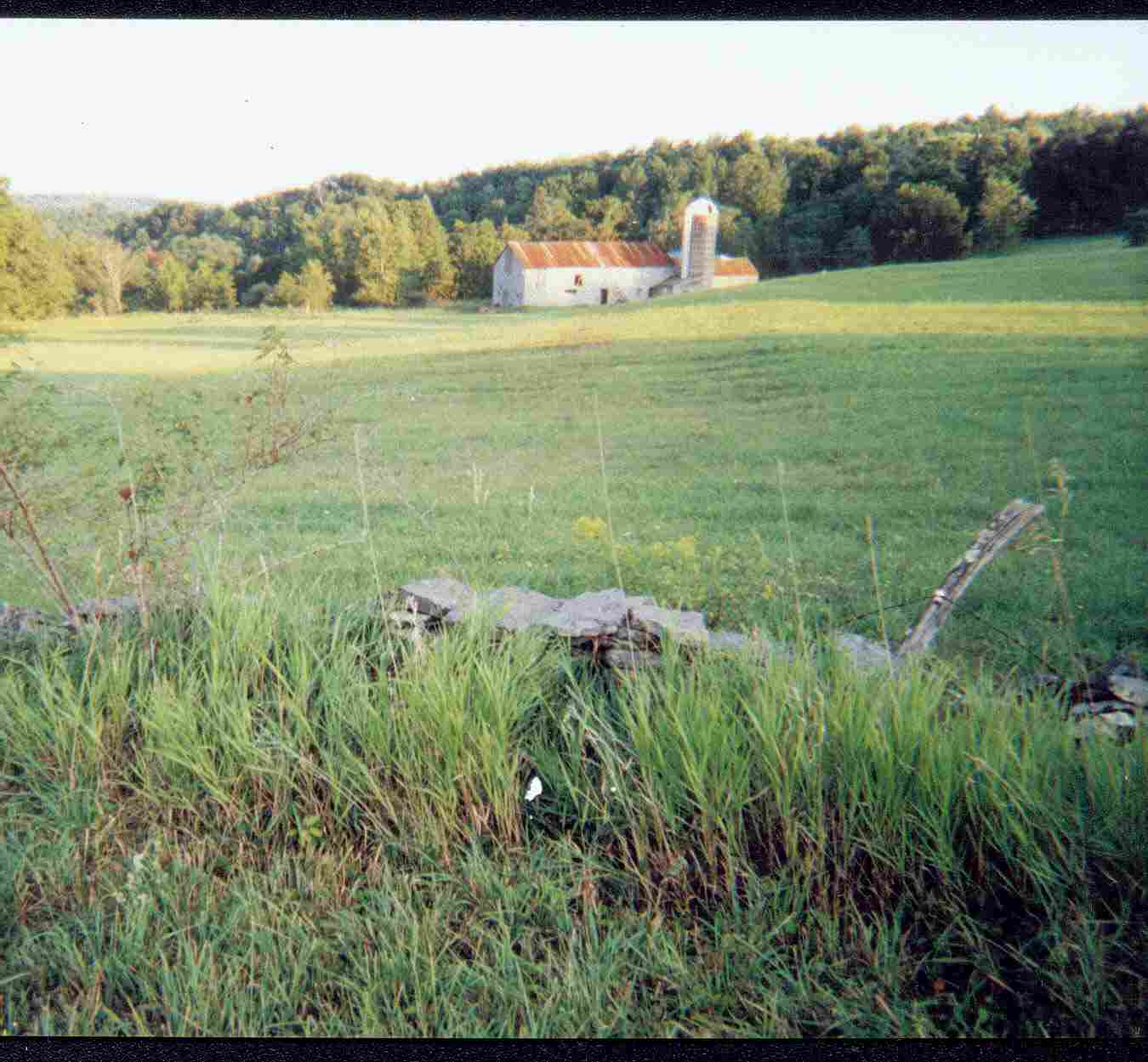

The Ten-Mile Meadow Project:

Preserving Land and Language

Ten-Mile Creek originates in Mysotis Lake in the township of Rensselaerville in southern Albany County. It flows down through the lush hamlet of Medusa, joining Eight-Mile Creek (from Westerlo) in thick forest near the end of South Street just north of the Greene County line, thence into Catskill Creek and eastward for roughly 25 miles to the Hudson River.

Ten-Mile Meadow consists of 100 acres of rolling grassland bordered on the east by the tree-lined creek and a favorite swimming hole used freely by residents until the early 80's with the blessing of then owner, dairy farmer Ed Walgren. Many still refer to it as Walgren's Farm. Though the farmhouse opposite was sold off, two barns still stand near the road, which leads a few paces down the hill to the bridge on Main Street with its general store and post office, firehouse and Medusa Church.

The Ten-Mile Meadow Project is dedicated to the acquisition and preservation of this land and water resource for local environmental and recreational benefit, and to the enhancement of community literary and artistic services, experience, and appreciation.

Medusa is home to about 150 families. A few residents are still grain, produce or dairy farmers, though most are engaged in other businesses--guest house or culinary, specialty shops, light industry--or practice a trade or profession, such as carpentry or teaching.

The hamlets of Preston Hollow and Potter Hollow, both as watermarked and mountainviewed as Medusa, comprise the rest of the township, itself part of a larger trans-county concentric, east to Westerlo, north to Middleburgh, south to Durham and Greenville, the central site of the most extensive shopping, banking, schools, and similar services in the area.

The community is stable, cohesive, and relatively prosperous, owing in large part to its natural beauty, which appeals to dual homeowners, sportsmen, vacationers, and retirees. Its active tourist board and arts council have won competitive state awards. It has readers and advertisers enough to support three weekly newspapers.

Those papers carried recent reports of a controversial proposed power installation in an historic river town 20 minutes east of Medusa, and of a cellular tower closer by. Whether such development is greeted as economic expansion or as economic encroachment depends on the individual mindset.

The Meadow could accommodate twenty houses on 5-acre lots: twice the number that make up all of Main Street now. Economic expansion or encroachment?

The Meadow is on the market now. Its owners, successors to Ed Walgren, live outside the community. They have held it for many years. Long enough, they believe.

Rockewn Ten-Mile Creek is loud. All that tumbling. Under the bridge, a waterfall. It roars in Spring. Audible up and down Main. And all along the east boundary of The Meadow. It takes about an hour to wade Ten-Mile downstream from the bridge to its meeting point with Eight-Mile, another hour upstream to its bridge near the cemetery. The deer were surprised to see a hiker.

The Meadow could stand some improvement. It was mowed lately--maybe to show off its topography, its stone walls. Some more wildflowers would be decorative, a few handfuls of seeds from the New England Wildflower Conservancy. A marker here or there, so children could learn all the names. A skymap too, for the nights lying on one's back, eyes on the layered stars.

For the barns, a broom, then a printing press and book bindery. Old newspapers on their way to the town dump, diverted and recycled.

Yeats set to music against the Ben Bulben-like outline of a Catskill rise. Hamlet's father appearing out of the mists of the moor. A kid's fish story--exaggerated, but somehow still believable.

(Medusa, July 2001)

~ . ~

We know you continually receive requests from arts, health, and other charitable organizations. No one can respond to every appeal. Nor do we expect to rely solely on individual contributions to realize this project. We are diligently prospecting among corporate, foundation, and government sponsors, expecting that they will bear the primary burden, though individual, natural persons enjoy the primary benefit.

Typically, you would be asked to select a monetary level of membership, offered benefits and privileges, designated a "friend," an "associate," a "patron." We've dispensed with all classifications but one: Be kind, if you will, generous, if you can.

And, by all means, indicate to us your preference for how your contribution should be used, i.e., whether for ___the acquisition, ___ the wildflower garden, ___ the book bindery or for ___ the literary and performance programs.

We ask that checks or money orders be issued in the name of The Author's Watermark, Inc., with the memo notation: "Ten-Mile Meadow Project."

Many thanks.

The Author's Watermark, Inc.

Box 1, Medusa NY 12120

(A not-for-profit corporation duly formed

under the laws of the State of New York

with its principal place of business in Medusa.)