nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Reviews

Fall 2014 / Spring 2015

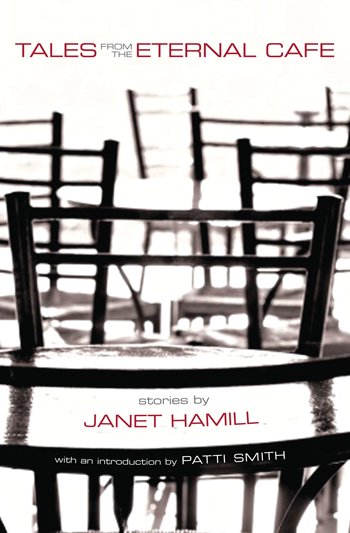

Tales from the Eternal Café

by Janet Hamill

Tales from the Eternal Café

by Janet Hamill

With an Introduction by Patti Smith

Three Rooms Press, 2014; 188 pages; $15.95.

ISBN-10: 0989512509/ISBN-13: 978-0989512503, paper

http://threeroomspress.com/authors/janet-hamill/

Reviewed by Diana Manister

With the publication of her new book,Tales from the Eternal Café, Janet Hamill achieves with a straightforward prose style what she has previously accomplished in poetry: a challenge to the way we habitually view reality. Her tales move along like conventional linear narratives until the reader realizes he is on a staircase in an Escher painting, navigating impossible conditions that appear in ordinary events: the artist Mark Rothko returns from the dead, for example, at a retrospective of his paintings at the Guggenheim Museum and engages the story's narrator in deep conversation. In another tale, a travel diary of a trip to Tangiers takes off on a magic carpet ride to the other side of logic.

Like Magic Realist writers, Hamill presents unlikely events as perfectly ordinary, something to be expected. In "Novalis" for instance, the lives of two men seem entangled across time and space after a magician buying props for his act at a Times Square magic shop learns of the mysterious disappearance of his friend, an illusionist known as Novalis of Coney Island, who literally vanished during a performance some months before.

As the story progresses, a series of seemingly impossible correspondences between Novalis of Coney Island and his namesake, the famed German poet Novalis, confound reason, creating an echo-chamber effect not unlike the one in Forster's >A Passage to India that so disorients Miss Quested that she cannot distinguish reality from imagination. When are two people, living in different times and places, one person? The two men in Hamill's tale share a pseudonym and eerily similar life histories: the first love of each, for instance, died before she was seventeen, causing both men to enter a dark night of the soul. Each man died around the age of 29 and they both wrote poems to the night in the same style, expressing a yearning to expire into the darkness and join their departed loves, as if two men could not only speak with one voice, but live the same life.

Readers looking for conventional plot development alone will miss the radical subtexts of these stories. Hamill's art is one of implication. Unlike narratives that establish standard chronology and resolve loose ends, her tales start in medias res, incorporate time slips, synchronicities and unsettled endings that leave a perceptive reader delightfully puzzled and, on reflection, a bit enlightened. Like Salinger and Hemingway among prose writers, she has mastered the art of meaningful omission.

Themes of doubling and disappearance, mysticism and magic run through the tales, presented as deadpan reportage. "Novalis" is again a case in point. Like a dropped pebble, the name generates ripples and reverberations. A little research into the biography of the 18th-Century Novalis reveals that he admired Friedrich Schelling, a philosopher influenced by Goethe who in turn inspired the Romantic vision. Schelling's metaphysics focussed on mystical revelation as a means of knowing reality. Unlike Hegel, he did not believe that rational inquiry alone could reveal ultimate truths. Schelling called the Protestant Reformation "unfortunate" for its rejection of the mystical element in Christianity. He deplored the Reformation's dismissal of the miraculous nature of the Eucharist as the actual presence of Christ in the bread and wine in favor of a pallid interpretation of the sacrament as a mere conceptual reminder of the Incarnation. For Schelling, the Eucharist offered an opportunity to understand reality beyond anything logic and common sense could offer.

In flagrant contradiction of Enlightenment rationalism, Schelling valorized the intuitive knowledge of truths that logic and linear thought cannot comprehend. Schelling's work impressed the English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who included many of his principles in the Biographia Literaria, where he distinguishes Imagination, which comprises transcendent vision, from the lesser faculty of Fancy, which does not. As Nicholas Kalmi notes in his recent book The Geneology of the Romantic Symbol, numinous images in the poetry of Blake, Keats, Shelley and other Romantic poets stand in opposition to the dualism inherent in Western metaphysics since Plato, uniting opposites in a synthetic elan. In Ode to a Nightingale, for example, the narrator is transported by the sound of a bird's song to a non-dualistic understanding of reality beyond the distinction of self and other, spirit and nature, past and present, here and there.

The Romantics regarded the Enlightenment as a catastrophic disenchantment of the world, because it disallowed the sacred and privileged the cogito as the summum bonum of human faculties. William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell wrote: "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern." It is precisely this attitude that Hamill's tales valorizes with narratives that jump the tracks, identities that exceed their boundaries, locations that transcend geography, and time that defies the natural laws we think are immutable. Logic alone, she implies, cannot bring illumination.

Novalis carried Schelling's transcendental agenda into literature with a style he called "Magical Idealism," dedicated to revealing truths that remain invisible when perception is corrupted by overly-rational belief systems. In his novel Heinrich von Offerdingen Novalis used a blue flower as an image in which opposites are united.

This transcendental aspect of Romanticism is inherent in both French Symbolism and Magic Realism, and also informs Hamill's Tales. The very first story in the book, "Baudelaire at the Prince of Wales," depicts the poet known as the Father of Symbolism during his last years in Brussels, attended by his faithful friend and publisher Coco Malassis, who narrates the tale. Baudelaire went to Brussels to seek an income as a lecturer and to find a publisher after Malassis went bankrupt. Both endeavors failed. Malassis, hiding out from his French creditors, assumed caretaker status for Baudelaire, who was suffering dementia as a result of advanced syphilis. In his addled state, Baudelaire in Hamill's tale breaks free of the normal constraints of space and time, simultaneously occupying the Prince of Wales café and the paquebot that once took him to India, mistaking his friend Malassis for the ship's captain and the waitress for his former mistress Jeanne Duval. He thinks he is aboard a ship: "Captain Saliz," he says to Malassis, "I find the rough seas no longer disturb me. Soon it will be evening and the stucco villas on the coast will pick up the glow of the moon."

Again, readers who interrogate Hamill's subject matter are rewarded with her text's rich implications. Baudelaire, despite his reputation for drugged sensual and emotional excess, achieved a new synthesis of empiricism and rationalism in poetry, describing states of consciousness that combine both ways of knowing the world. Critics, scholars and translators often miss his poetry's serious epistemological challenges. In the two poems that best manifest his ars poetica, "Elevation" and "Correspondences, opposites unite in the narrator's transcendent imagery. Sounds, aromas and tactile sensations escape the usual categories, nature is no longer external, and the 'living symbols' of the natural landscape look back at him with a familiar gaze. Self and other are one and the same. For Baudelaire, the luminous symbol transcends the limits of Cartesian thinking, and performs the synthesis that language cannot achieve because it separates subject and object, noun and verb and the tenses of time.

Symbolism and art that derives from it attempt to restore the unreasonable ecstasy of transcendent knowledge that the Enlightenment largely removed from human experience. Just as in the work of Baudelaire the physical world provides the portal through which the sacred arrives, Tales from the Eternal Café, re-sacralizes the mundane world. It actualizes the vision of Shelley who said poetry "strips the veil of familiarity from the world, and lays bare the naked and sleeping beauty which is the spirit of its forms."

Like the so-called Magical Realist writers Gabriel Maria Marquez, Juan Luis Borges and Italo Calvino, Hamill's stories recommend a disposition of openness to the impossible becoming possible, to things formerly separate merging in unity and to the magical as something to be expected. A recurring leitmotif in Tales from the Eternal Café is the conflation of identities. "In the Patio of the Orange Trees" the voices of several narrators nestle within each other like Russian dolls. An anonymous narrator explains:

"In 1963, shortly after the restoration of Cordoba's Mezquita, Dr. Julio Gayangos, chief of restoration, told this story to Emilio Garcia Gomez at the Café Horno de San Luis on Calle del Corregidor."

These three voices speak as one, telling the tale of a naïve temple stonecutter who, in an act of automatic writing, inscribed a poem written by an 11th Century Andalusian poet, Ibn Hasm, whose writing celebrated the divine revelations of early Muslims in that very place. Different moments in time become simultaneous, voices merge, and the result is transcendence of time, place and individual identity.

Doubling also occurs in "Blue Corpus Christi," set in the Café Belmonte in Grenada. Senorita Flores, an actress in Garcia Lorca's La Barracca theater troupe, tries to persuade her brother, who is grief-stricken and enraged over the murder of his lover, to travel back with her to her home in Madrid. Set in Andalusia during the Spanish Civil War, the atmosphere is thick with the dark menace that resulted in the assassination there of Garcia Lorca himself under circumstances never explained. Details surrounding the deaths of both the lover and Lorca duplicate each other to such an extent that the identities of the two men merge.

The allusion to the sacrament of the Eucharist signals the story's subtext. Corpus Christi is Latin for "body of Christ." It is the only Christian holy day focused solely on transubstantiation, the mystical presence in the bread and wine of the body and blood of Christ. Although Corpus Christi was a major holy day for believers in medieval Spain, who celebrated it with mystery plays re-enacting the attendance of the Magi at the birth of Jesus, the post-Enlightenment world reduces supernatural awareness to superstition, and regards the Magus as either deluded or a fraud. No longer do we revere wise men who are open to miraculous signs and portents, or find mystical transport in the sacrament of the Mass. In "Blue Corpus Christi" Senorita Flores hungers for spiritual nourishment, but finds it is no longer available. She orders "some of the Corpus Christi Carmelite crescents" but is told

"Senorita is too late, they're all gone.

But there are other sweets.

"No. I had a craving for those little

yellow crescents. I think of them when I think of the festival."

The Carmelite nun who petitioned the Church for the addition of Corpus Christi to the calendar had experienced a mystical vision of the Eucharist under the moon. Her awareness of the spiritual dimension of the sacrament was uncorrupted by intellectual doubts or Cartesian separations; she believed in the impossible presence of Christ in the bread and wine, just as the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation believed the stranger who said "What is impossible for man is possible for God."

The bible of course is full of possible impossibles. Sarah and Abraham, for example, who conceive a child in extreme old age. After the Enlightenment however, after Nietzsche, Marx and Freud rationalized the old gods out of existence, the old Emperor of the World was no longer all-powerful. Are we then bereft of transcendent meaning and grace?

The impossible, however, does happen in the secular world. We are discovering that nature at the subatomic level often behaves in supernatural ways: particles can spin in two directions at once, and communicate over vast distances instantly, as if time and space were illusions; a single photon can pass through two openings at the same time. Magical events form the very basis and foundation of reality. Perhaps certain artists, capable of intuition and imagination, are able to sense and evoke such hidden realities, providing new ways of beholding the sacred lurking in the everyday.

Magical correspondences, for example, proliferate in Hamill's story "Tangiers Dojoun" when the narrator, shaken by the earlier discovery of a hex figure placed among her things in her hotel, is menaced by men in the Café Fuentes who call her a whore. Vulnerable and endangered in a society that frowns on a woman alone in a café, she is rescued by a dog who appears out of nowhere, like a shamanistic power animal who comes to her aid when she has no earthly recourse. She calls him Sebsi, after the Moroccan kif pipe, a hint that he is a facilitator of altered perceptions that can open the portals to a new kind of knowledge. After all, didn't Genet, Burroughs and Ginsberg visit Tangiers for that very purpose? The protagonist of 'Tangiers Dejoun" finds a city where belief in the sympathetic magic of voodoo still hold sway, where pouches filled with feathers, herbs, snakeskin and semi-precious gems are carried for protection and a piece of clothing or strand of hair can be used to cast white or black magic spells on the owner.

In this endeavor she is in good company. Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez made bizarre events seem possible, even likely, as when a woman in One Hundred Years of Solitude disappears into the sky while folding laundry. He even described miracles that seem humdrum, like the bedraggled angel in "An Old Man with Enormous Wings" who is blown to earth by a rainstorm. Marquez protested that our ideas about reality are too limited, and proclaimed himself a realist.

Likewise, the writing of Jorge Luis Borges describes moments of transcendent understanding. In "The Aleph" the narrator complains that the syntax of our grammar is inadequate to the impossible vision experienced by a man in a cellar in Argentina:

In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful, not one of them amazed me more than the fact that all of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency. What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write will be successive, because language is successive." (A Borges Reader, 160-61.)

Like Borges' Ficciones, Hamill's Tales from the Eternal Café offers literature that is explicit as narrative but enigmatic at the thematic level. By following the threads she weaves through the tales we find her meaning: revelation is possible in ordinary life beyond the restrictions of logic and limited views of reality; magic happens every day; not to believe in it is a failure of imagination.

Diana Manister writes literary criticism for The Modern Review; Forum, The College English Association Journal; BigCityLit and About Contemporary Literature.com. She is a member of the International Critics Association and the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics and writers. Her poetry has been published in Four and Twenty, Maintenant, a Dada Journal Vols. 5,6,7,8; Big Bridge, The Ozone Park Journal, The Sheepshead Review; The New Post-Literate; Ygdrasil and anthologies. Her poem "Hubble" was set to music by composer John Raeger and premiered in Oakland and San Francisco in 2013, performed by the Piedmont Choirs conducted by Robert Geary, and in Helskinki Finland in 2014.