nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Reviews

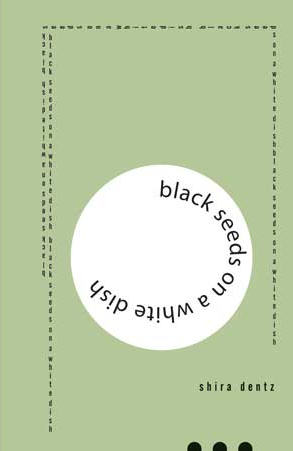

Seeds of Life — A Review of Shira Dentz's

black seeds on a white dish

black seeds on a white dish

by Shira Dentz

Shearsman Books; 2010; 90 pages; $15.00

ISBN: 978-1-84861-128-3, paper

http://www.shiradentz.com/?page_id=7

Reviewed by Laurel Kallen

In Shira Dentz's first book of poetry, black seeds on a white dish, the poet shows us how seeds contain life, how life often manifests as desire, and how the seeds of life already contain their future demise. Is it coincidence that the title image, "Black seeds on a white dish," occurs in "Poem for my mother who wishes she were a lily pad in a Monet painting"? (74) The poet explains that she and her mother "just don't come apart." In other words, the-mother-is-the-daughter-is-the-mother-is-the-daughter, ad infinitum. As for the unquenchable nature of desire, the reader has only to pause before the wish to become a lily pad in a painting! Two layers of impossibility amuse and trouble us here — first, the impossibility of becoming a lily pad and, second, the impossibility of becoming anything that exists only in a work of art.

Dentz learned early on how seeds contain their own death. In the collection's opening poem, "The Grasses Unload Their Grief," the poet evokes, as she does often, the death of her brother when both he and she were young children. In the poem, a field of grass casts off the family's tragedy as it is "mowed" by their walking, "one leg following the other curved like scythes, turning with / the measure of blades rippling in a field." (13) This mowing happens despite the poet's assertion that "[o]ur feet didn't touch the ground all year." The grass seems to have been cut by the family's loss. Similarly, during the year of mourning, the mother in the poem diminishes her speech. The speaker in the poem says that her mother "uttered syllables" rather than words and her father, rather than speak, "blew cinders." (13) The terseness of these images leaves the reader poignantly, and appreciatively, bereft.

In "Limn" (18), although the seeds have grown into flowers, the flowers are short-lived. The poet explains that "Flowers have lips — their petals, / dispersing phrases as they die." Flowers — and, by extension, people —speak as they die and, thus, live fully in the very process of expiring. Poets, in particular, must sing their swan song. Just such an eloquent passage from vitality to death is evident in "Numbness and shade,"(19) with its "[v]oices supple as leaves in their prime, / drying here and there, unstemming." As with "feet not touching the ground" above, here the leaves are "unstemmed." Death is an uprooting.

While many of the poems in this collection are concise, half-page or whole-page free-verse lyrics, several are written in form or in longer poetic sequences. In one sequence, "Rorschach: Last Week, the moon dipped close to the gray streets, a surprise guest, huge and yellow," (22) the poet's seed/garden imagery returns. The speaker sees "the night sky as a place / like a garden." Later on, "a shadow sprouts." In all of these images, the death/life dichotomy persists and intrigues. How fitting that bisexuality, which emerges a few stanzas later, erupts into images of two different fruits, "cherry round, red sweet, / banana, also sweet" and then is immediately followed by the monostich "Embers." The seeds of love contain the possibility (inevitability?) of their own demise. Embers can be fanned into flame or die. The flower returns as "man- / love freshly shedding /" contrasted to "between women [pulp of a flower]."

In "Birdsong," (29) longing is a nest of "Twig and whatever leaves go into its making." The lifeless twigs create — give life to — a nest, but the nest is filled with longing, an emotion that can perhaps be best understood as a yearning for "life," and all that is unattainable within it, and an awareness of impending "death" or limitation.

In an untitled, pantoum-like poem (35), the stanzas again play with seeds, blossoms and the reality of fading. First, there is loss and aging, "Gone, like a cuff link. / Creaselines on my father's forehead." Then, new life erupts as "A crocus blossom cracks through." At the beginning of the next stanza, the "creaselines" repeat and then "A sunflower yolk falls down sleep's chute; / springtime in the unconscious. / A blazing, Yellow circle." In the final stanza, "Seeds [are] flung back over my shoulder." Will they germinate? If so, how? Will the poet look back to see what has become of them?

What becomes of seeds is not a given. In "I carry" (43), the speaker reminds us that plant growth is not always life-affirming; it can, in fact, suggest a corpse: "What does my brother, lifeless, look like? His body steady in the landscape / a shaft of wheat in a field."

Love, too, is full of leaves, blossoms, and decay. In "To the New Lover," the poet turns an experience of betrayal into a voyeuristic, if skeptical, understanding of what the betrayer is experiencing with her new love. Leaves, flowers and fruit characterize this adventure, too.

A rustle whooshes leaves on branches,

Charms tinkering on a bracelet.

Sky, in place of leaves,

This shiny afternoon.

You finally got your passion: A woman

With the panache of a gay Frenchman,

3 blue early-autumn days,

Trees in full bloom—

Setting the table just for you.

You teem with each other's fluids,

inhale her cologne (Jil Sander's Feeling Man).

She perches strawberries and grapes on your teeth,

watches your tongue flip them back.

Disaster impends for the speaker until she confidently predicts that when the new girlfriend eventually "untwines from" the speaker's lover, she will add insult to injury by saying "how medieval it is / not to forgive betrayal." Perhaps the intellectual character of this response adds to its sting. We know how hurtful it is when we, impassioned, are faced with a calm, cool, collected opponent.

In "Ex-utero," (61) the speaker mourns the end of a relationship with a woman she has loved,

when I think of her

I see the curve of a melon.

flesh tipped forward,

the seeds stripped out,

hung together with goo.

Fruit, so often the image associated with fertility and the prime of life, is equally linked to violence and gore, as in the "goo" holding together the stripped-out seeds of a love destroyed.

Desire, too, is messy. In "Up the Wazoo River," the poet struggles with this problem, again sampling fruit as she goes along.

I think I know the precise extent of my desires, i.e.: half a banana,

please.

This makes me not even want the damn banana.

The big deal thing was finding I had moved while eating, I wanted

the whole banana. (68)

The problem of desire, then, is that it always changes and, thus, never dies. But, here, the poet asks if we want it to die. The appearance of cherries and "Lean apples [that] spar across planks" in the succeeding lines highlights the frustration inherent — and inescapable — in desire. Paradoxically, though, desire enables us to feel fully alive. "The red peel next to the green avocado looked promising," says the poet in "slip" (73). Desire, with its attendant frustration, swells again in "A Ritual" (89) when the speaker asks "why seduce with pictures when sex is out of the question." Having posed this question again and again, Shira Dentz leaves us contentedly in her garden as she embarks on a "wait for rain" (89) and decides to "leave bouquets out in the sun" (90). These poems will re-seed upon each reading. Their sometimes stark, always compelling, images and lyricism invite us to revisit the garden often. After all, some seeds will be watered and blossom; some will dry up; some will be tossed over one's shoulder; others will remain latent and desirous, stark and immanent — black upon a white dish.

Laurel Kallen is a poet and fiction writer who teaches at the City University of New York. She is the recipient of the 2009 Stark Short Fiction Award and the Teacher/Writer Award. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Global City Review, Legal Studies Forum, The One Three Eight, La Petite Zine, and Atlanta Review. Her collection, The Forms of Discomfort, will be published by Finishing Line Press in July 2012. Laurel has been a featured reader at Perch Café, Cornelia Street Café and The CUNY Graduate Center. She was a speechwriter for former New York City Mayor David Dinkins. Laurel holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York and an MA in French from UC Berkeley. She is an attorney admitted to practice in New York and New Jersey. Her daughters, Maia and Chloe, are strongly opposed to their mother's presence on Facebook.