nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Reviews

Fall 2011

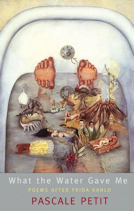

What the Water Gave Me, Poems After Frida Kahlo

by Pascale Petit

What the Water Gave Me,

Poems After Frida Kahlo

by Pascale Petit

Black Lawrence Press, 2011; 64 pages; $14.00

ISBN: 978-0982876657, paper

http://pascalepetit.co.uk/index.php?f=data_poetry_collections&a=0

Reviewed by Lynn McGee

What the Water Gave Me, Poems After Frida Kahlo, by Pascale Petit was published by Seren Press in Wales in 2010, and by Black Lawrence Press in the U.S., in 2011. The collection was shortlisted for both the T.S. Eliot Prize and Wales Book of the Year, and was a Book of the Year in London's Observer.

The poems in this stunning collection center on the paintings of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, and the book is titled after Kahlo's 1938 self-portrait which presents the artist submerged in a bathtub, images from her turbulent life adrift on its cloudy surface.

What the Water Gave Me is the fifth poetry collection by Pascale Petit, a French/Welsh poet living in London, UK. Trained as a sculptor at the Royal College of Art, Petit's poetry resonates with a deep trust of symbol and the image. Co-founder of Poetry London and that magazine's Poetry Editor for 15 years, she teaches poetry courses at Tate Modern that examine image making, and her own work reflects indigenous and other cultural narratives from her travels to the Venezuelan Amazon, China, Kazakhstan, Nepal, and Mexico. As Australian poet Les Murray, in the Times Literary Supplement puts it, "No other British poet I am aware of can match the powerful mythic imagination of Pascale Petit."

Clearly, it had only been a matter of time before the "powerful mythic imagination" of Frida Kahlo attracted the focus of poet Pascale Petit. Her poems in What the Water Gave Me explore the complex iconography of Kahlo's work, which chronicles her difficult life, and unique resolve to overcome it.

Diagnosed with polio at the age of six, Kahlo was encouraged by her father to take up sports, including boxing, to rebuild the muscle in her atrophied right leg. She wore a shoe with a built-up heel, to equalize the length of her legs, and was already on a determined course to defy the physical limits set before her, when she was caught in a horrific bus crash.

That broadside collision with a trolley car left the teenaged Kahlo with a broken spinal column, broken pelvis, crushed right foot, and other serious injuries including those caused by an iron hand rail that pierced her abdomen and uterus. She eventually was able to walk again, but lived the rest of her life with agonizing, intermittent pain, and endured an estimated 35 operations; a botched spinal fusion, gangrene, infected bone grafts, and a number of painful miscarriages—all of which she vividly confronts, in her art.

The events of Kahlo's life have attracted much popular attention, but it is her use of those events as the subject of her work that links the poems in this collection. In the Author's Note to What the Water Gave Me, Petit writes, "…this book is not a comprehensive verse biography and some aspects of her [Kahlo's] life are not included, mainly because I wished to focus on how she used art to withstand and transform pain."

What Petit has done, in fact, is to take that transformation one step further—to interpret seamlessly beyond it, speaking in Kahlo's voice with a quietly compelling, first-person narrative.

It is not necessary to have the corresponding Kahlo paintings at hand, to feel the shocking intimacy, despair and unnerving tenderness of these poems. The book's cover does show one Kahlo painting, What the Water Gave Me, after which it is titled. Six poems throughout the book are based on that painting, and present the milestones of Kahlo's life, as Petit sees them.

Speaking as Kahlo in "What the Water Gave Me, (I)," we see the artist's pre-crash, fetal self:

my budding body sheathed in pearl

as I learn,

even before birth,

to doodle in the dark.

The bath water remains amniotic in "What the Water Gave Me (II)," and from it, emerges Kahlo's miscarried infant daughter:

The water opened

into the vortex of my daughter's face.

Her skin was a rippled mirror.

In "What the Water Gave Me (III)," that which contains (and sustains) her, has become a playmate; the bathtub is animate, light-hearted, crawling on claw feet, ferrying Kahlo

…into the cactus garden,

delivering me to my dinner guests

with a triumphant splash.

More ominously, the bathtub appears as a sarcophagus in the fourth poem in this series, "the water about to become kerosene," as the bus crash nears on the timeline of Kahlo's life. And in the fifth poem, the gravely injured Kahlo has begun to rescue herself with art:

…my one-thread brush

grafting skin…The current shivers like shaken glass

splashing my legs with shoals of pigment—

the blue sting, the red ache,

how art works on the pain spectrum.

In "What the Water Gave Me (VI)"—and the last poem in the collection—Petit, speaking as Kahlo says, "This is how it is at the end," and suggests that the artist ritualistically embraced, rather than denied her pain:

Water, you are a lace wedding-gown

I slip over my head, giving birth to my death.

I wear you tightly as I burn.

This poem closes with a survivor's hard-won perspective: "don't make me come back"—reflecting, perhaps, the ambiguous, hand-scrawled note left by a dying Kahlo as she lay hospitalized for pneumonia, still recovering from the amputation of her right leg, and having joined Diego Rivera— despite doctors' warnings—in a public rally decrying North American intervention in Guatemala, less than two weeks earlier.

Kahlo died in 1954 at the age of 47, leaving behind a body of work that weaves indigenous Mexican religious symbols with surrealist elements in some of the modern Western world's most unsettling and transformative self-portraits and other paintings.

"My Birth" is a Frida Kahlo painting often referred to as one of her most intimate. The viewer faces a woman's wide-spread legs, where the huge head of a newborn Kahlo emerges, and with steely accuracy, regards the mother who is birthing her:

…her legs are my arms,

her sex is my necklace.

As with other poems throughout the book, Petit deftly extends this painting's images by inferring its intention:

I swivel my emerging head

so you can recognize me

by my joined-up eyebrows…

Even my unhappiest paintings

will be joyful…

The birth mother's breasts, in this poem "…will never feed me," says Petit as Kahlo, and in the next poem, "Suckle," an infant Kahlo with a disconcertingly adult head lies in the lap of a self-made source of sustenance:

My nurse is Mexico—

one breast is Popocatèpetl,

the other, Lake Xochimilco.

Petit guides us through layers of the painting, presenting Kahlo as both the infant, and the painter of the infant:

My ear opens its canal

to listen for the hunger-cry

…the trembling

rings of earth's throat—

when I finish those baby lips

so they can suckle.

In the poem titled after the painting, "Remembrance of an Open Wound," Petit envisions Kahlo's troubled marriage to the renowned Mexican muralist Diego Rivera—Kahlo's "second accident," she famously writes. This painting shows a seated Kahlo—her petticoat raised to reveal a splashy, bleeding wound—and in the poem, she speaks to her groom:

Whenever we make love, you say

it's like fucking a crash—

…Neither of us knows when the petrol tank will explode.

In this poem, the handrail that impaled Kahlo in the bus accident ages her instantly, and she becomes,

a crone of sixteen, who lost

her virginity to a lightning bolt.

And in a swift blending of scenes that reveals the painting's underlying emotional narrative, Petit transposes the accident with the wedding bed:

It's time to pull the handrail out.

I didn't expect love to feel like this—

you holding me down with your knee,

wrenching the steel rod from my charred body

quickly, kindly, setting me free.

Kahlo's marriage with Diego Rivera was notoriously problematic. They both engaged in extramarital relationships—including Kahlo's affair with the married Leon Trotsky, and Rivera's affair with Kahlo's younger sister, Cristina. Those thorny times, coupled with Kahlo's lifelong physical pain, are braided into themes deeply embedded in the paintings, and animated throughout the book.

In the end, despite Kahlo's struggles, artistic vision wins; a point Petit circles and returns to. The spine may be broken, but "…every vertebra has an eye," she writes in "Self Portrait with Monkeys," and in "The Two Fridas," Petit as one Frida says of the other,

Her palette is my heart sliced in half

…Strange how it keeps beating,

turning blood to paint.

In "Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (II)," Petit illuminates—as she does in other poems, as well—the biographical facts of Kahlo's life, envisioning her youthful career aspirations:

Before a streetcar rammed me

I was going to study medicine,

had already glimpsed betrayal

through a microscope—the way microbes

breed in a soundless frenzy.

Another poem, "Self Portrait with Cropped Hair," features the well-known painting of Kahlo seated in a kitchen chair, newly shorn, and striking a stalwart pose; legs apart, feet planted on a floor littered with strands of just-cut hair, which Petit conducts to life:

…my snake-locks rise

from the floor, dance like musical staves

and sing that old folksong you used to whistle…

Readers can infer that in Kahlo's world, nothing stays dead for long, or is discarded without ceremony—not pain, not hair, nor experience of any kind.

In a sense, then, What the Water Gave Me gives center stage to a gleaming ladder out of hell. Fifty-three poems spiral from 42 paintings. Readers familiar with Kahlo's work as well as those who aren't, will read the book with a liberated sense of how narrative and image can reset our assumptions about art, and its potential to heal.

In that way, the poems say much about Frida Kahlo—but they also say something about the poet who is drawn to her work, and remakes it in another form. There are no biographical clues related to the maker of these poems, no hints at the poet's own struggles or personal demons—but Petit writes with an insider's uncanny intuition. In the end, I think, What the Water Gave Me even makes a place for the reader's own struggles to reverberate with recognition, and be refashioned into something beautiful.

Lynn McGee's poems are forthcoming in The American Poetry Review, Tilt-a-Whirl, and Blue Stem. Two of her poems were just published in Big City Lit, and two recently appeared in The New Guard; one a finalist and one a semi-finalist in that magazine's contest judged by former U.S. Poet Laureate Donald Hall. Other poems of hers have appeared in the Ontario Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Sun magazine, Phoebe, Pittsburgh Quarterly, The Southern Anthology, Laurel Review and other journals. Her poetry chapbook, Bonanza, http://www.writerscenter.org/bonanza.html won the Slapering Hol national manuscript contest; she also received a MacDowell fellowship, and earned an MFA in Poetry from Columbia University.