nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Reviews

Fall 2011

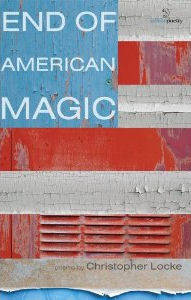

End of American Magic

by Christopher Locke

End of American Magic

by Christopher Locke

Salmon Poetry, 2010; 76 pages; $21.95

ISBN: 978-1-907056-53-6

http://www.salmonpoetry.com

Reviewed by Rachel Bennett

Memories don't arrange

themselves neatly, like beetles

pinned in straight black rows:

they're a house of cards

after one breath.…

Building on this play (from the poem "Still Life with School Bus"), Christopher Locke's End of American Magic is a game of 52 Pickup. Nearly every poem within the collection's three sections contains a lasting image, whether of an alliterative grasshopper with "wings / clicking like a baseball card / in bicycle spokes" or a heart as "a small bird before it discovers / a windshield." The poems attempt to work through the speakers' addictions, desires and labors of many sorts. They stitch together family histories, parents as children, lost brothers, unborn babies. But the best parts are less stitched, come closer to "the sea crashing indifferently / against this world of heat / and land."

Franz Wright, many of whose poems also emerge from hauntings and dark corners, said, "I thought if I wrote something successful, then I could live my life and feel good. I had everything backwards. First, you fix your life. Then, you will be in a position to say something in art." Locke's poetry embodies this act of fixing, of making sense, of looking back and finding in yourself everything that has come before. Like America itself—also a work in progress—the book houses characters from many walks and times: dream-eyed immigrants, mentally ill men and the parishioners who try to call down God, students baking lemon meringue pie, Korean War soldiers, disillusioning lovers, a small girl with a small tin horse, Cuban tobacco workers, the man waiting for his sentence. Taken together, absorbed and then recalled, these apparitions quilt together something less warm than real. You might think about the weight of your own ghosts.

But the images. For me, this book is most successful when the images do not serve masters ("Let us show you / the failures of your life," or the boy whose life was "a permanent echo"—lovely!—"found / slumped in his truck, / pistol dangling from / his small-boned hand") but stand free and apart and are just themselves. So, in "No Siesta":

…The bronchial

mesh of mesquite trees stiffens

the air, and birdsong unplugs

its numerous fountains under

this blue of tight hours, of heat

translucent in its heavy broth

of light.

You don't need more than this. You come away wanting the fallen house of cards, and it's okay if some of the deck remains lost. Locke is at his best when there is no explanation or summation, when the light—a recurring theme—can just be, and when we as readers aren't even given a place or epigraph as mooring. One poem bravely opens with Ashbery: "I've tried each thing, only some were immortal and free." I wonder about the combination of immortality and freedom here, a combination that suggests both terms are necessary pieces of what the poet is getting at: a thing can be immortal yet pinned— Locke's black beetles—or free and destined to pass away. For me, magic in this collection begins and ends with the latter, with the breathing and unencumbered image. These images, far more than their stories and mooning notions of loss, remorse, shame, etc., stick with you and speak something bigger about the world and our little place in it.

Paradoxically, Locke suggests that perhaps our biggest time, our realest time, is as children, and several poems introduce younger spirits. There's the girl with the small tin horse, of course. There's the man recalling the freedom of playgrounds. But fear is present here, too: "Childhood frightened you, reduced / your heart to a pity of leather." And one poem sees "young / lives troubled by what you choose / to say or leave out." It's as if to say that first there are imagined terrors, and then the terror becomes bodied—and we can wonder which is worse. The English poet John Betjeman said that childhood "is measured out by sounds and smells and sights before the dark hour of reason grows," but Locke suggests that darkness is always a companion, and the most we can hope is to squirrel away a bit of light. In this book, images are as acorns stored for winter, briefly reclaiming what Dickinson calls the "sacrament of summer days" even against the sound of December's fist on the door.

Children relish the image, the smell, the taste, as heedless of meaning as of checkbooks and cocktail parties. Casting back at some receded plain, Locke remembers, "the invention felt good / on my tongue." It is always like this for the child, and, vaguely glimpsing this part of yourself, you might wish there were more such simple pausing and relish here, more "brown barns steam[ing] / in August mornings like loaves / of unsliced bread," more "thunder / kicking darkness in all / its awkward falling." Locke writes, "When there was / nothing left to break, we stood dumbly, / waiting for an answer." But sometimes an answer is not what we need. We might just ask, Why? And again. Sometimes, we might just stand and "see the house / fill with light, resplendent as if / emptied from pitchers carved / from the bluest air."

Rachel Bennett has a BA in English from Grinnell College, where she won two Whitcomb Poetry Prizes judged by Gerald Stern and James Galvin, and she is an alumna of the Iowa Writers' Workshop Irish Writing Program in Dublin. Her poetry, which has received two Pushcart Prize nominations, has appeared in Avocet, Big City Lit, Blood Lotus, Buffalo Carp, elimae, I-70 Review, New Madrid, Rhapsoidia, Smartish Pace, The Portland Review, and zafusy. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.