nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Fiction

Fall 2011

Rock Dude

Roger Hitts

''Have you heard 'Bloody'?" I asked my friend Tom with a knowing wink. We were riding on a bus packed with the altar boys from St. Michael's Catholic Church of Maple Grove, Michigan, on our way to the church's annual baseball outing at Tiger Stadium, going to watch what ended up being a good raking by the Tigers of the informidable Steve Dunning and the Cleveland Indians.

''No," said Tom, "Who's it by?" I answered Deep Purple. We had set up — a scheme — there was no ''Bloody" by Deep Purple. But that day on the church trip, then on the school bus each day for a week thereafter, each one of us in on the scheme, one by one, claimed to have heard ''Bloody." Best fucking song ever, Ritchie Blackmore really outdid himself this time, we would chirp. And each day our friend Toilet Taylor would glumly say he hadn't heard it yet. Now, we all know one: Toilet was that inevitable outsider who tried to inhabit each band of friends, the one who wanted so hard to fit in he would go to any lengths to be cool, to be part of the group. We knew our plan would work.

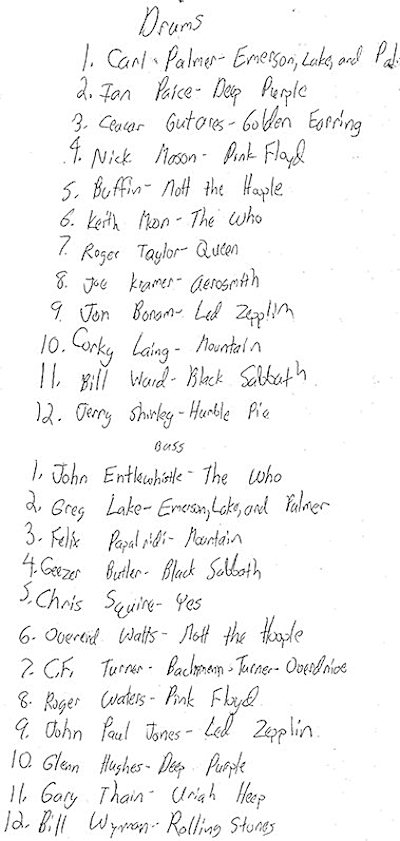

Understand that, in 1974, we were junior high musical zealots, and we treated music like we treated sports. Each week, in a four-ring binder, we would all vote and rank each group in terms of ''who was the best!" Even more absurdly, we kept a Top 10 list of the best guitarist, bassist, keyboardist, drummer — pretty much based on who played the fastest and with the most intricacy. When one of us would buy an album we never heard before, say Derek and the Dominoes' "Layla and other Love Songs," we would chirp up, ''Didja hear Clapton on that record! He's going up to No. 3 on my guitarist list this week — I gotta move Alvin Lee down a notch!" We were rock 'n' roll bobos who talked about musician talent in the same manner we would talk about the trade that brought Rusty Torres and Charlie Spikes over to the Tigers. Sports and rock were kinda the same thing to us.

Still, looking back, there was something incredibly organic about it all. We weren't city kids, we weren't suburban kids — we were so rural they had to bus us twelve miles to the nearest town with a school, and even that town didn't have so much as a traffic light. Garage rock? We did it one better — we had barn rock. My older brother was a bassist in a mainly-covers band called Rapture — current New York art rockers, they were there first! When they weren't playing the local Elk's Lodge, treating old-timers to their versions of the latest from Robin Trower, Uriah Heep and Black Oak Arkansas, they practiced in an old barn on our 80-acre farm. And when they weren't practicing, my friends and I would take on the considerable task of taking apart my stereo system, trucking it out to the barn, then playing records while we strapped on Rapture's instruments and mock rocked ourselves to the point of ecstasy. We were particularly adept on ''Got This Thing On The Move" by Grand Funk Railroad — hometown heroes and all. My brother eventually did an 8-year stint as bassist for ? And The Mysterians — he graduated from the barn to the garage.

We lived in the middle of nowhere, and our fragile eggshell minds, as Jim Morrison would say, were incredibly influenced the Creems, Rock Scenes and Hit Paraders that arrived in our mailbox. By 1974 these magazines gave considerable space to the burgeoning glam scene, and we were taken in hook, line and sinker. Soon my friends and I all owned the Dolls albums, bought Mott The Hoople and ventured into the brave new world of Raw Power. These bands and their musicians rarely graced our Top 10 musician lists — we weren't stupid, Johnny Thunders had no business being on a list with Jimmy Page, unless it was for drug intake. But these bands that were short on musical talent but long on attitude and fresh songwriting co-existed peacefully with the Blue Oyster Cults and Rushes that we idolized.

But glam died a short and somewhat painful death, and by the time we were ready to graduate in 1978, disco ruled the airwaves and punk ruled the underground. We rejected both camps — disco, well for obvious teenage dolt homophobic reasons wasn't for us, and punk rock had all of the awful musicianship of glam rock and none of the joy. Trouble was, by this time, big ole dinosaur rock was getting pretty crappy, too. Homer Simpson was probably right when he said rock achieved perfection in 1974. By '78, we were left with the sour likes of Journey, Styx and REO Speedwagon, and newer rock bands like Van Halen were just a little too ironic for our tastes.

By college we were breathing fumes from the tailpipe of punk rock, but embraced wholeheartedly that new-fangled major record label inspired concoction called New Wave. The music gets a bad rap — rightfully so in many cases, when you think of The Cars and their ilk. But new wave to us was also XTC, Psychedelic Furs, Gang of Four — they might not fit the standard definition of what New Wave is now considered historically, but they were the post-punk world to us in 1982. I became editor of my college newspaper and immediately hired myself as chief record reviewer, mainly to score all the freebies the labels were sending to our campus. Alternative rock, called college rock then, was burgeoning and those greedy labels saw gold in them thar hills of college kids.

Sure, we made missteps along the way. I remember Tom and I heading 150 miles south to Detroit to catch the coolest of new bands, Big Country. A band with a set list so pitifully short they played their eponymous hit twice in an hour. We raved about them in the school paper, but Big Country ran out of gas before they had even filled their tank. I assigned a friend to review The Alarm's first album, and he raved that they were ''The Clash, except for more intelligent politics." Go figure.

It took years of growing out of our musical short pants before we went back and caught up with what we really missed that was right under our nose growing up in Michigan — The MC5, Sonic Rendezvous Band. Turning into a pro writer and interviewing the likes of John Sinclair helped fill some gaps. We would travel from Bookie's in Detroit to the Agora in Cleveland to the Aragon in Chicago to catch the bands that made us whole — Ramones, Husker Du, Black Flag and the like. By that time, we had completely disowned the hard rock of our youth — we were much too fucking cool to be caught dead listening to Ten Years After.

Anyway, back to the story. After a week on the school bus, and each one of us talking in increasingly breathless tones of the masterwork that was ''Bloody," Toilet Taylor hopped the bus steps one day with a very satisfied, Cheshire cat grin on his face. He produced a cassette tape and asked, ''Can you guess what I have here? BLOOOODY!" It was our time to pounce. ''Toilet, there never was a 'Bloody,' we just made it up." Toilet turned beet red, sunk in his seat. He would make half-hearted attempts to join our conversation, but he knew it was no use — he had been had, but good, and had demonstrated his uncoolness once and for all to the world as he knew it.

Looking back, I still feel like shit for doing that to Toilet, and not just for the endless psychiatric bills, dime bags and toothless hookers he must have encountered later in life. After having lived in New York City for the past 22 years, I've put up with more than enough hipsters who only listen to the hippest, latest tracks — if it didn't come out in the last 48 hours, it isn't worth a damn. The exclusionary politics of the reigning dance scene in New York is laughable to the extreme. I often feel like piping up when I get into some conversation with some Eurotrash deejay, ''Yeah, but have you heard 'Bloody?'"

Life was simpler when Creem magazine told us what to do and Lester Bangs was our God. And to this day, dammit, I think there's nothing wrong with liking Steppenwolf and Stereolab just the same.

Roger Hitts is a two-time United Press International Columnist of the Year who currently works in network television. As a writer, Hitts's by-line appears in dozens of magazines in the U.S., Europe and beyond. He lives in Sunnyside, Queens with his wife Daphna and daughter Liana.