Reviews

In the Shadow of Wings — Laurie Byro's The Bird Artists

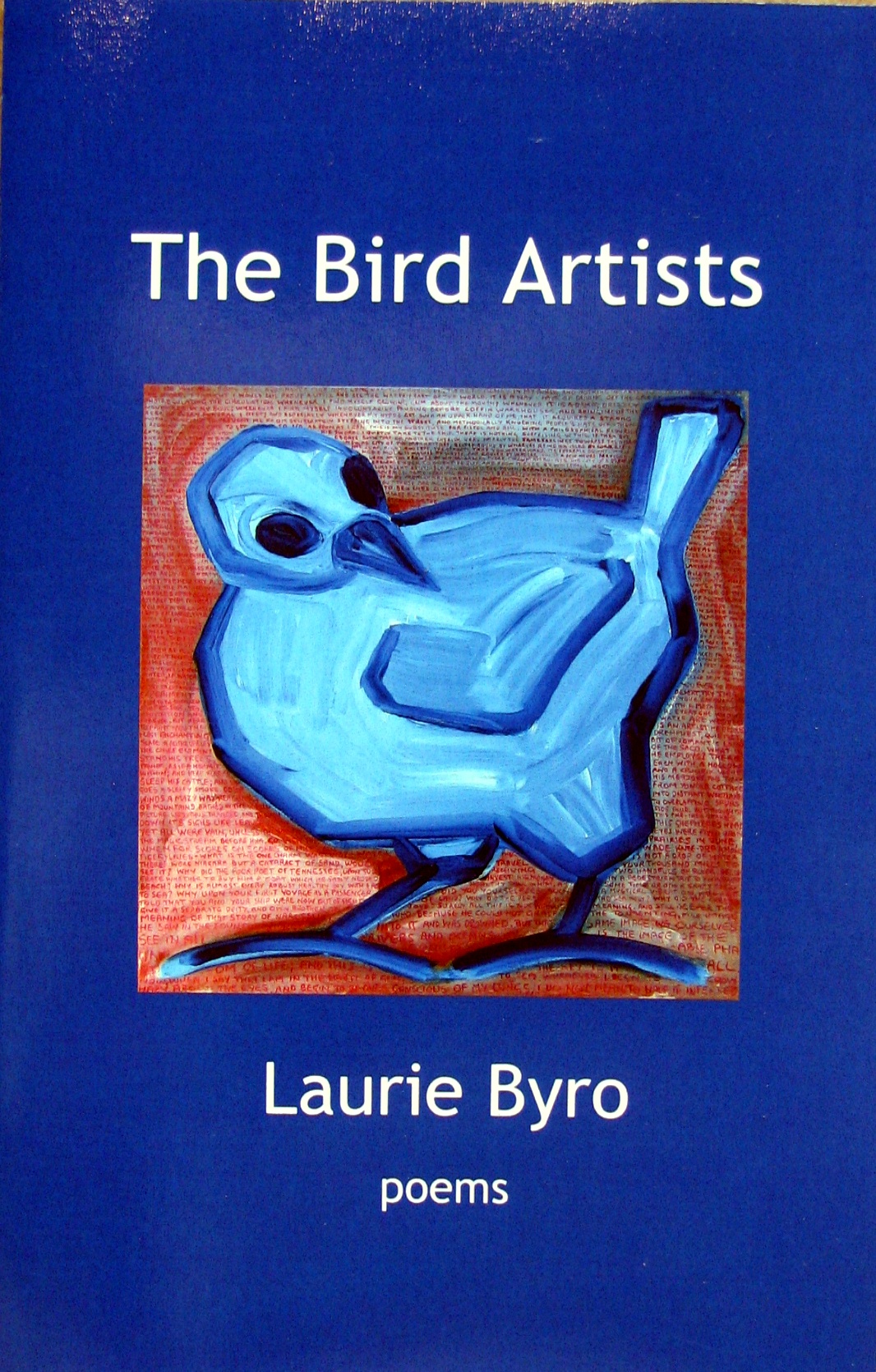

The Bird Artists

by Laurie Byro

H&H Press, 2009; 26 pages; $10.00

ISBN 978-1-61539-948-2, paper

Reviewed by Diana Manister

At least since Homer turned sailors into swine, animal symbolism has proved to be a handy device for depicting human experiences, usually of the baser sort. Blake and the later Romantic poets, especially Keats, valorized the animal energies that the Enlightenment had repressed. As Robert Bly describes the process in his book Leaping Poetry, non-human states became a favored topos of modern poets as stand-ins for the self.

The Bird Artist positions Laurie Byro's work in this tradition. Densely imagistic poems developed as poetic conceits take the form of extended metaphors in which the speaker is a wolverine, a raven, even an insect with a hangover. These non-human personae facilitate Byro's exploration of intensely personal themes:

Cotton-mouthed, hung over, I wake up

in my sooty dress somehow ashamed to be seen

in the utter waste of daylight. The barbecue

with all those mint juleps was intense but I strayed

too long on the edge of a glass….

In the above excerpt from "Living in the Body of a Firefly" the narrator-insect confides private fears, "the danger/ in the deep-throated baritone of frogs." Transformations occur in nearly every poem: a wolf speaks, apples become a fox, a serpent becomes a troubadour, the moon blows kisses, a child appears as an orchid and a pink bud, a woman as a brown thrush and a magpie.

Like Io changed into a cow or a servant girl to a furry weasel in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Byro's transformed humans enact her speakers' affinity with organic nature:

…I swill

shadows and rain down my parched throat,

flood my mouth with a curse. I leave worms

thick with blood back on my windowsill

to be borrowed, to be used up….

Byro's gift for creating vivid images and marrying sound with meaning is striking throughout the book: "When I suck my fingers, I am as fair/as the dollops of honey I scrape from the last queen's hive" she writes in "Devon Song," and in "My Mother's Bones" …Mother, I carry your bones in a paper sack/like a picnic lunch." Rather than ornamental however, her use of anthropomorphism feels like a necessity, as if no other device could convey the particularities of the female experiences her poems address.

Though indebted to Plath's use of chthonic imagery to express psychological agons, Byro's poems are less grotesque, and less bitter, rarely achieving Plath's vicious hiss. Though a few of the poems in this impressive collection depict murderous rage, they lack Plath's corrosive acid. "Wolf Dreams" describes mating and fertility coming to nothing but anger and a desire for revenge;

"All that winter I peeled

and sucked papery bark for the sweet taste.

…I gave birth

to his amber-eyed bastard who without hesitation

he devoured…

I shall make myself

a meal of him, savor his voluptuous tongue,

and suck all the bitterness from his bones…

"Devon Song" is written as if Plath herself were speaking, voicing resentment toward the husband who drives off "to teach slim hipped sophomores how to kiss, how to parse a poem," leaving her in the country with bee hives, rabbit traps, slaughtered rodents and nosy neighbors. It was during the time Plath and Hughes lived in Devonshire that she discovered his infidelity and their marriage collapsed, but also the time she composed her famous sequence of bee poems, casting herself as the abandoned queen

Plath often cursed nature, which had largely taken away her artistic freedom, especially when she faced single motherhood with two small children. Beyond feminism and all gender politics, female artists have an argument with nature that male artists do not. A shadow enters Byro's poems at the point where art and biology conflict. Male anatomy remains the same during the bearing and nursing of children, while women's physical nature asserts itself, at the expense of the needs of the ego.

In a significant sense, art is not created by the living. A kind of death attends the ten-thousand hours it is said art requires of the artist seeking mastery, a passion to which the natural life of the body is indifferent as it exercises its own imperatives. Plath to her credit was alone among women poets in her time in giving voice to her discomfiture in this regard. Her final journal, which her husband destroyed "so her children would not have to read it," apparently exposed more of her rage than was compatible with good mothering.

The poets Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop and Marianne Moore were not required to reconcile their artistic ambition with the demands of motherhood, while Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton tried to have it all and failed, opting for suicide. Byro addresses this dilemma with poems whose emotional tone is moderate, which avoid both hatred of anatomical destiny and the warm and fuzzy sentimentality that mars much of women's poetry on the subject.

Byro pays tribute to another woman writer, Virginia Woolf, also a suicide. "Virginia Sings Back to the Stones in Her Pocket" is rich in allusions to Woolf's biography. Its title refers to the stones with which Woolf weighted her coat before wading into the River Ouse to drown. The poem contains some of the most grotesque images in the collection:

…This one lay on the couch

With her eyelids peeled back, mushroom

Capped stones rattling in the crèche of her

Eye sockets.

The asexual, childless Virginia is compared to her fertile sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, who lived in a house full of children and sustained a ménage with both a husband and a lover:

She pictures the summer table noisy with

Anemones and her sister's brood…

The stones will do their job

Shortly….

Byro's poems as they appear concatenated in this volume develop an ongoing though not linear narrative of psychological crisis, a series of disturbances in which the body's natural life makes claims on the speaker that conflict with the life of imagination, of art, "I steal the eggs/of jays. I sip delicate shells clean/through the membrane, yellow with suns."

In "Dinner with the Ghost of Rilke" the speaker is apparently the poet herself, addressing the author of the shamanistic "Sonnets to Orpheus" whose echo occasionally can be detected in this volume. "Secrets, For W.S. Merwin" hints at an unnamed childhood trauma: "Me with my old/coat mended so neatly where I had sewn secrets into its pockets." A dark spirit haunts this collection, a real danger to which Byro's narrators are vulnerable, torn as they are between the spirit that soars and the animal life drawing them earthward.

Diana Manister is New York City poet who has featured at such venues as the late lamented punk rock club CBGB's, St. Mark's Church Poetry Project, The Living Theater, Bowery Poetry Club, Poetry Unnameable, the Lyric Recovery Festival at Carnegie Hall, as well as at colleges and universities.

A Contributing Editor of Big City Lit, she is also an elected member of the American Branch of the International Critics Association (AICA). Her poetry reviews appear regularly in The Modern Review and online at BigCityLit, about.com, small press exchange and artezine. Her poems have been published and exhibited in print and web publications including PoetryRevolt, Autumn Sky, Salonika, Big Bridge, Waterworks, The Cleave, artezine.com and others, and in the print anthologies Distance from the Tree and The Company We Keep from Headwaters Press and Best Online Poetry of 2008 from Poetry Blog Rankings.